Translate this page into:

Cyclosporine in dermatology: Evidence-based review with a special focus on recent updates

*Corresponding author: Dr Anupam Das, Department of Dermatology, KPC Medical College and Hospital, 1F Raja SC Mullick Road, Kolkata 700032, West Bengal, India. anupamdasdr@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Dutta B, Naiyer N, Das A. Cyclosporine in dermatology: Evidence-based review with a special focus on recent updates. Indian J Skin Allergy. doi: 10.25259/IJSA_9_2025

Abstract

Cyclosporine (CSA) has been used by dermatologists for decades, and this remains one of the most preferred options for treating a wide gamut of dermatological conditions. Although it is US- Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for limited number of disorders, it is prescribed as an off-label drug for numerous conditions. Psoriasis, urticaria, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, alopecia areata, and atopic dermatitis are some of the indications for which CSA has been studied extensively. Besides, there are many other conditions such as polymorphous light eruption, chronic actinic dermatitis, vitiligo, Hailey–Hailey disease, granuloma annulare, systemic sclerosis, and cutaneous lupus erythematosus where there are isolated reports of successful use of CSA. Off late, voclosporin has been FDA-approved for lupus nephritis, and its pharmacokinetic properties have placed the drug higher to CSA. This review is an attempt to comprehensively outline the indications (both approved and off-label), dose, monitoring protocol, and guidelines for using CSA in dermatology.

Keywords

Atopic dermatitis

Cyclosporine

Psoriasis

Urticaria

INTRODUCTION

Cyclosporine or cyclosporine A (CSA) is a lipophilic cyclic polypeptide containing 11 amino acids, found in Tolypocladium inflatum and Cylindrocarpon lucidum.[1]

Initially, CSA was introduced for the prevention of hyperacute and acute graft rejection as well as for graft versus host disease, owing to its immunosuppressant and anti-inflammatory properties, which were beneficial. Later on, CSA showed its efficacy as an anti-inflammatory agent in various dermatoses, and in 1997, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved its use in dermatology for the treatment of psoriasis.[2]

With over three decades of clinical use, CSA has been found to be effective in treating various skin conditions, including psoriasis, atopic dermatitis (AD), and other inflammatory and immunological disorders.[3] In the era of biologics, which are used in a variety of dermatological conditions, the conventional systemic immunomodulators like CSA are being considered lesser than usual. Nonetheless, CSA has some advantages over newer agents in producing broad-spectrum, immunomodulatory effects on the immunopathogenesis of several dermatological conditions. This makes it efficacious and useful even in this era of biologics. Hence, in this review, we emphasize the merits and demerits of CSA which needs to be re-considered and re-assessed in the new age of biologics.[4]

METHODOLOGY

A comprehensive English literature search across multiple databases (PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE, and Cochrane) for articles on the use of CSA in dermatological conditions was done using the keywords (both MeSH and non-MeSH, alone and in combination) “cyclosporine,” “psoriasis,” “atopic dermatitis,” “vitiligo,” “childhood dermatoses,” “alopecia areata,” and “vitiligo”. The levels of evidence and grade of recommendations have been delineated as per the criteria laid down by the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy and Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.

MECHANISM OF ACTION

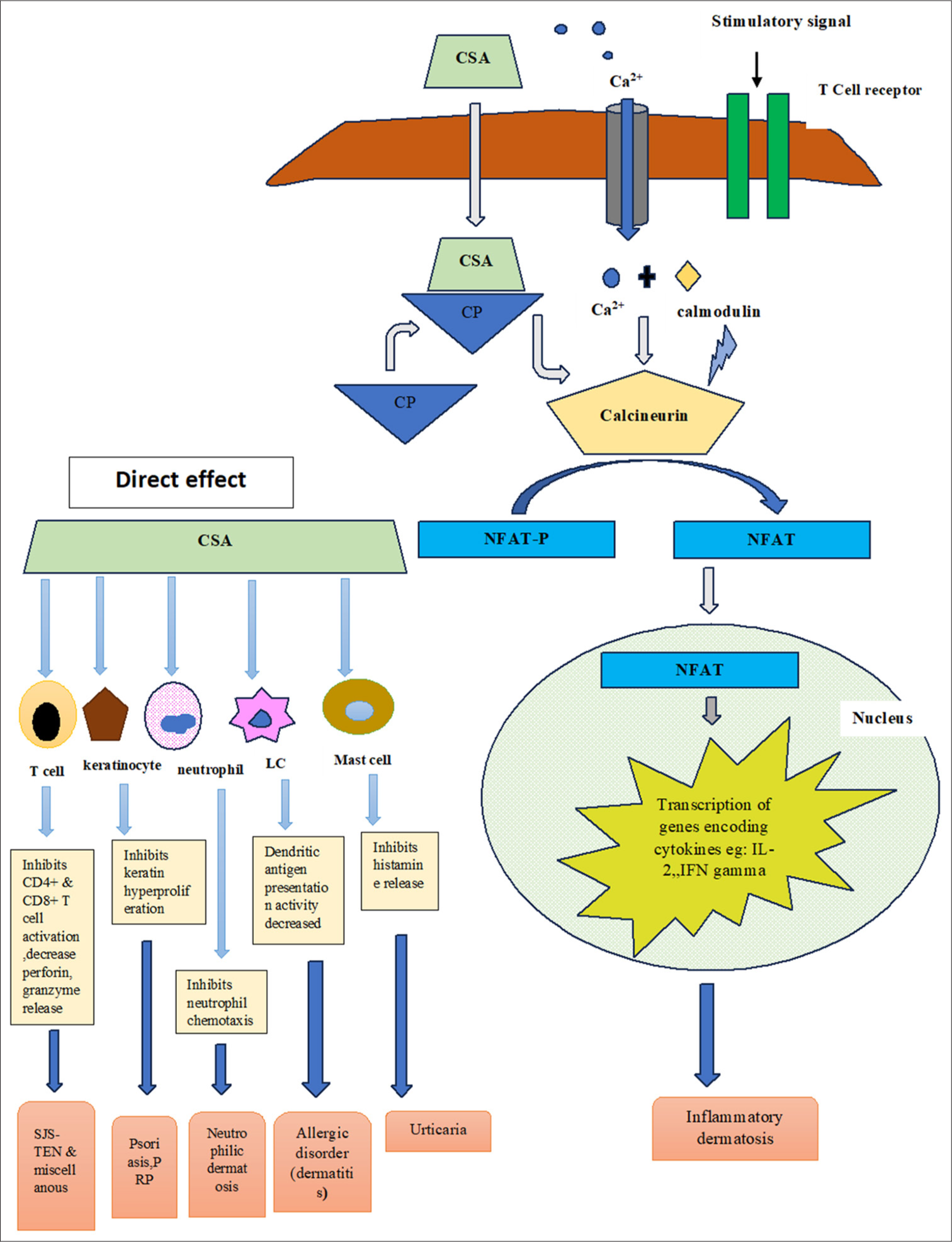

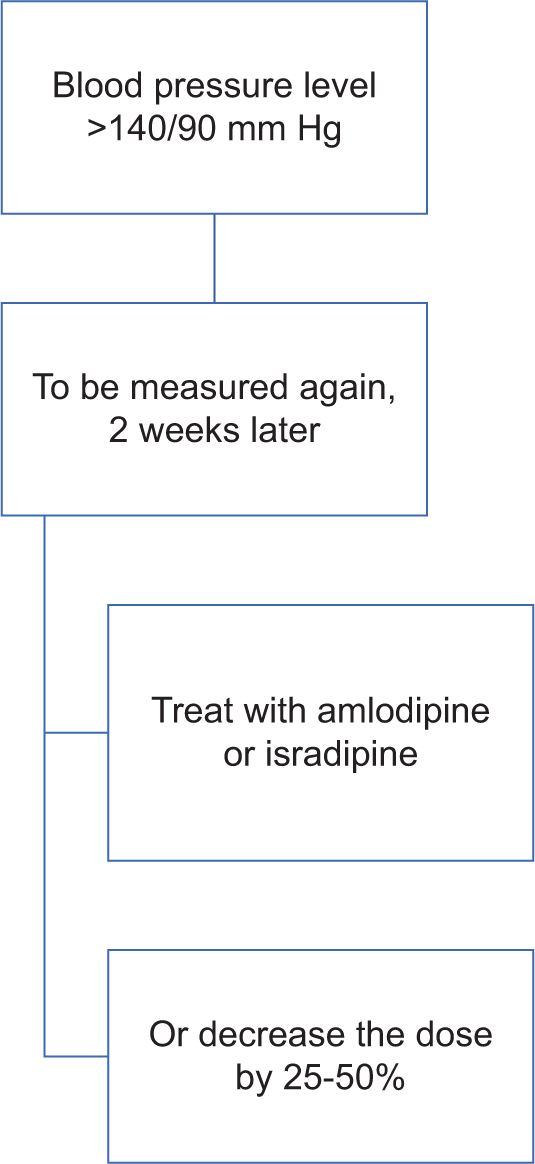

The mechanism of action of CSA is not yet fully elucidated. It works as a calcineurin inhibitor, thus inhibiting the synthesis of interleukins (specifically interleukin-2 [IL-2]), responsible for self-activation and differentiation of T lymphocytes. The drug inhibits the lymphocytes in the G0 and G1 phases of the cell cycle [Figure 1]. It primarily targets the T helper cells, apart from suppressing the T suppressor cells. The T lymphocyte–B lymphocyte interaction crucial for the activation of B lymphocytes is also subject to inhibition. Additional research has shown that it inhibits CD4+ CD25+ Tregs, eventually causing blockade of the host immune tolerance.[4]

- Schematic diagram showing the mechanism of action of cyclosporin in various dermatoses. CSA: Cyclosporin, CP: Cyclophilin, NFAT: Nuclear factor for activated T cells, IL: interleukin, IFN: Interferon, LC: Langerhans cell, PRP: Pityriasis rubra pilaris, SJS-TEN: Stevens johnson syndrome-toxic epidermal necrolysis.

PHARMACOKINETIC PROPERTIES

Metabolism: Metabolized through CYP3A4, into one N-methylated derivative (AM4N) and certain hydroxylated metabolites, namely A hydroxylated derivative (AM1) and Another hydroxylated derivative (AM9).

Enzyme interaction: Inhibits CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein. Half-life: 8.4–27 hours.

T-max: 1.5–2 hours.

Excretion: The drug is primarily excreted through bile into the feces.

Dosage: Adults: 2.5–5 mg/kg/day, children: 3–5 mg/kg/day. Factors altering the absorption: Duration, post-transplant diet, gastrointestinal condition, biliary flow, hepatic function, length of small intestine, and vehicle used in the formulation.[4]

USES OF CSA

CSA is mostly used as a “rescue drug” or “induction therapy,” mostly for a period of 6 months. However, particularly in the pediatric population, it is still used as a maintenance therapy for a period of up to 1 year. Initially, CSA was approved only for moderate-to-severe psoriasis, and later on, it has been tried in a wide gamut of other inflammatory skin disorders, as an off-label drug.[1] Table 1 highlights the FDA approved and off label indications of cyclosporine in dermatology.

| FDA approved | Off-label use |

|---|---|

| Psoriasis • Severe • Recalcitrant • disabling |

Eczemas • Atopic dermatitis • Chronic hand dermatitis • Dyshidrotic eczema • Perthenium dermatitis Papulosquamous disorders • Lichen planus • Pityriasis rubra pilaris Neutrophilic dermatoses • Bechet’s disease • Pyoderma gangrenosum • Sweet syndrome Alopecia • Lichen planopilaris • Alopecia areata Granulomatous dermatoses • Granuloma annulare • Sarcoidosis Adverse drug reaction • SJS-TEN • AGEP • DRESS • Photosensitivity dermatoses • Chronic actinic dermatitis • Polymorphous light eruption Urticaria • Chronic idiopathic urticaria • Cold urticaria • Solar urticaria Autoimmune connective tissue disorder • SLE • Dermatomyositis • Systemic sclerosis Others • Vitiligo • Eosinophilic cellulitis • Morphea • Prurigo nodularis • Reiter’s disease • Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of Ofuji Kimura’s disease |

FDA: Food and Drug Administration, SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus, SJS-TEN: Stevens-Johnson-Toxic epidermal necrolysis, AGEP: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS: Drug reaction eosinophilia with systemic symptoms

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory disorder, mediated by T helper 1 (Th1)/Th17 T cells, and dendritic cells, leading to elevated levels of IL-17, IL-23, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). The cytokines eventually cause increased proliferation of keratinocytes, and cutaneous vasculature, and influx of inflammatory cells into the psoriatic lesions.[5] Attributed to rapid onset of action and effectiveness, CSA remains one of the most preferred alternatives in treating psoriasis.

Indications of CSA in psoriasis:

Severe flare-ups

Recalcitrant psoriasis

Disabling psoriasis

Major life incidents, where rapid clearance is needed.

Chronic plaque psoriasis

In practice, CSA is typically used to induce remission at a daily dose of 2.5–5 mg/kg for 3–6 months.[6] The magnitude of response and rapidity of clearance of lesions are dose-dependent. However, the chances of adverse events also increase, with an increment in dosage. Therefore, dosing should be individualized and adjusted based on efficacy and tolerability. Some studies suggest that pulse administration of CSA for a few days weekly can be effective for both inducing and maintaining response in psoriasis patients.[7]

The relevant studies have been highlighted in Table 2.[8-17]

| Author | Year | Type of study | No. of patients | Age | Dose and duration | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marsili et al.[8] (Italy) | 2022 | Observational, cross-sectional, multicenter study | 196 patients | Mean age=46.6 years Range= 18–89 years |

5 mg/kg/day for≥12 weeks | For response categories, 39.8%, 22.4%, 16.8%, and 20.9% of patients were responders, suboptimal-responders, partial-responders, and non-responders to CSA treatment. Overall, 28.6% of patients permanently discontinued treatment with CSA. | Patients were only partially satisfied with CSA treatment, reporting measurable impact on quality of life. Only 40% patients showed a satisfactory response to CSA. |

| Singh et al.[9] (India) | 2021 | Randomized control trial | 133 patients | Group 1: (Mean age-38.04±14.97) Group 2: (Mean age-38.77±15.03) |

Group 1: MTX intramuscular injection 0.3 mg/kg/week. Group 2: combination of MTX intramuscular injection 0.15 mg/kg/week plus CSA 2.5 mg/kg/day orally rounded off to the nearest 25 mg in two divided doses. |

The achievement of PASI-75 (P=0.005), PASI-90 (P<0.001) and PASI-100 (P=0.001) was more in the combination group (Chi-square test) | The combination of reduced doses of MTX and CSA is more efficacious with earlier onset of action and similar adverse effects as with MTX monotherapy. |

| Oh et al.[10] (South Korea) | 2018 | Prospective observational study | PsO=82 patients PsA=18 patients |

PsO=34.15±16.11 years PsA=41.74±15.36 years |

3–5 mg/kg/day tapered by 1–1.5 mg/kg according to treatment response |

The results suggest that CSA has considerable therapeutic effects on arthritic symptoms in PsA. This is the first study to compare clinical characteristics between PsO and PsA patients and to evaluate treatment responses to CS |

Considering its potential benefits for retarding joint destruction, appropriate use of CS in patients with PsA may be a valuable therapeutic option. |

| Di Lernia et al.[11] (Italy) | 2016 | Multicentric retrospective study | 38 patients | Up to 17 years Mean age= 12.3 years |

Median dose= 3.2 mg/kg/day Range=2–5 mg/kg/day for 1 to 36 months |

Fifteen patients (39.4%) achieved a complete clearance or a good improvement of their psoriasis defined by an improvement from baseline of≥75% in the PASI at week 16. Eight patients (21.05%) discontinued the treatment due to laboratory anomalies or adverse events. Serious events were not recorded. | CSA was effective and well-tolerated treatment in a significant quote of children. CSA, when carefully monitored, may represent a therapeutic alternative to the currently used systemic immunosuppressive agents for severe childhood psoriasis. |

| Bulbul Baskan E et al.[12] (Turkey) | 2016 | Retrospective study | 22 patients | Less than 18 years | Mean therapeutic dose=3.47±0.62 mg/kg/day for a mean duration of 5.68±3.29 months | Seventeen patients were found to be excellent responders. The median time to total clearance of the lesions was 4 weeks. |

We conclude that cyclosporine A therapy is equally effective and safe in pediatric psoriasis patients as in adults. |

| Fernandes et al.[13] | 2013 | Randomized controlled trial | 21 patients | Range=27–60 years Mean age=44.3±6 9.9 years |

4 mg/kg/day for 12 weeks (induction phase), 19 patients were randomly allocated to receive either 5 mg/kg/day for 2 consecutive days on weekend or continued 2–3 mg/kg/day for 20 weeks |

There were no significant differences between the 2 groups before starting the maintenance phase with regard to the mean PASI score (P=81% Moreover, at the end of the study PASI 75 was achieved by 80% and 75% of the patients on weekend and continuous therapy, respectively. | Both treatment regimens showed comparable results. The mean daily dose was higher in the continuous therapy group (2.6 versus 1.4 mg/kg/d) and the twice weekly dosing schedule was more convenient for patients. |

| Shintani et al.[14] (Japan) | 2011 | Randomized controlled trial | 40 patients | Group A=100 mg once daily Group B=50 mg twice daily |

The improvement rate was 69.4±4.8% in group A and 73.4±4.3% in group B. PASI-50 was achieved by 82% in group A and 84% in group B. At 6 weeks, the number of patients with PASI-50 was significantly higher in group A than in group B. PASI-75 and -90 were also achieved in both groups with no significant difference between groups. | Administration of a fixed-dose cyclosporine microemulsion (100 mg/day) is practical for second-line psoriasis treatment. | |

| Yoon et al.[15] (South Korea) | 2007 | Randomized controlled trial | 61 patients | More than 18 years | 2.5 mg/kg/day starting dose and an increasing regimen (“standard regimen”) or a 5.0 mg/kg/day starting dose and a decreasing regimen (“step-down regimen”) group for 12 weeks | According to a 50% PASI reduction (PASI 50), the response rate at 12 weeks was similar for two groups. The percentage of patients achieving a 75% PASI reduction (PASI 75) at 12 weeks was higher in the step-down regimen group. The mean time to PASI 50 or PASI 75 was shorter in the step-down regimen group. | This study suggests that the “step-down” cyclosporine regimen offers an effective and safe therapeutic option for the management of severe psoriasis. |

| Kokelj et al.[16] (Italy) | 1998 | Open clinical trial | 20 patients | Initial dose 4.5 mg/kg/day, dose reduced by 0.5 mg/kg/day every 2 weeks after clinical assessment. Calcipotriol ointment was also applied over unilateral lesion only |

Eighteen patients completed the study. 17 of the 18 presented more evident improvement on the side treated with combined therapy, while only one patient showed a better result on the side treated with cyclosporine alone |

These results underline the effectiveness of the combination of calcipotriol and cyclosporine in order to decrease the total dosage of cyclosporine. | |

| Meffert et al.[17] (Germany) | 1997 | Clinical trial | 133 patients | 1.25 or 2.5 mg/kg/day or placebo for 10 weeks (Period I), up to 5 mg/kg/day for 12 weeks (Period II) |

After 10 weeks the percentage improvement from baseline in the PASI was 5.9% on placebo, 27.2% on 1.25 mg/kg/day and 51.0% on 2.5 mg/kg/day CSA. The final average dose at the end of study period II was 2.99 mg/kg/day. At this time the PASI was reduced by at least 75% in 63.0% of the patients. From this group of good responder no patient relapsed (PASI>50% of baseline) during the 4 weeks after termination of active treatment |

1.25 mg/kg/day is superior to placebo in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris and that a dose reduction to 1.25 mg/kg/day should be considered in patients responding well to a conventional dose between 2.5 and 5 mg/kg/day. |

PASI: Psoriasis area and severity index, PsO: Psoriasis, PsA: Psoriatic arthritis, CSA: Cyclosporine, MTX: Methotrexat

Erythrodermic psoriasis

CSA is considered a first-line therapy for acute and unstable cases according to the published consensus of the US National Psoriasis Foundation in 2010.[18] Table 3 highlights the summary of studies demonstrating the efficacy of CSA in erythrodermic psoriasis.[19-22]

| Author | Year | Study type | No. of patients | Dose | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bruzzese et al.[19] (Italy) | 2009 | Case report | Single patient | 3 mg/kg/day | Complete cure of infliximab induced erythrodermic psoriasis within 3 months. | CSA is effective in therapy for psoriasis induced by anti-TNFαdrugs. |

| Franchi et al.[20] (Italy) | 2004 | Open-label study | 24 patients | CSA 200 mg/kg (divided into two daily doses for 3 weeks; dose was titrated down to 100 mg/kg for 2 weeks The 311 nm radiations were produced by PHILIPS TL01/100 W lamps |

The PASI score showed a decrease of about 90% (PASI time 0:23.9–67.2 - mean 56.4; PASI after 9 weeks: 2.1–10.3 - mean 5.45). All patients were responders. |

Study confirm the effective symptoms control in patients with erythrodermic psoriasis poorly responsive to treatment of a new therapeutic approach which combines a reduced dose of CSA with UVB phototherapy |

| Kokelj et al.[21] (Italy) | 1998 | Case report | 3 patients | Combined therapy with CSA and etretinate | Clinical response was prompt to the combined therapy. The two drugs were tapering off gradually over 6 months; the patients maintained the remission for prolonged period. | Combined CSA-etretinate therapy may be considered as an effective and well tolerated treatment of erythrodermic psoriasis in patients not responding to monotherapy regimen. |

| Giannotti et al.[22] (Italy) | 1993 | Uncontrolled Open multicenter study | 33 patients | 5 mg/kg/day (initial mean dose 4.2 mg/kg/day) Slowly tapered after remission by 0.5 mg/kg every 2 week |

After 6.3±3.4 months, CSA doses of 3–5 mg/kg/day had led to complete remission in 67% of patients in a median time of 2–4 months; in a further 27% of cases, considerable improvement in skin involvement was observed, with a reduction of more than 70% in comparison with baseline | Low dose CSA can be considered as the therapy of choice in patients with erythrodermic psoriasis. |

PASI: Psoriasis area and severity index, CSA: Cyclosporine, UVB: Ultraviolet B, TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α

Pustular psoriasis

Due to the rapid onset of action, CSA is considered a valuable treatment option for pustular psoriasis as well as first-line therapy for generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy.[23] Table 4 shows the use of CSA in pustular psoriasis.[24-27]

| Author | Year | Study type | No. of patients | Dose | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Georgakopoulos et al.[24] (Canada) | 2017 | Case report | Single patient | 200 mg/kg/day in two divided doses for 2 weeks | Dramatic improvement in disease symptoms including clearance of pustules | This case report supports the use of CSA as a first line agent in rapid symptomatic relief for flares |

| Hazarika[25] (India) | 2009 | Case report | 2 patients | 3 mg/kg/day, dose was gradually tapered and stopped after 3 weeks of delivery | The skin lesions started regressing dramatically from second days onwards and complete resolution after 2 weeks | CSA can be an option in the management of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy or psoriasis with pustulation in pregnancy. |

| Kiliç et al.[26] (Turkey) | 2001 | Case report | 3 patients | 1–2 mg/kg/day for 2–12 months | Clearance of psoriatic lesions occurred after 2–4 weeks of treatment | CSA is effective and tolerable therapy for generalized pustular psoriasis |

| Fradin et al.[27] (USA) | 1990 | Case report | Single patient | Initial dose of CSA 7.5 mg/kg/day; then slowly tapered off | PASI score reduced from 33.6 to 14.9 by 4 week. PASI score was 0 by 16 week. |

A slow decrease in the CSA dosage (0.5–1 mg/kg/day monthly) may be more effective in maintaining remission of the disease |

PASI: Psoriasis area and severity index, CSA: Cyclosporine

Nail psoriasis

CSA can be used in nail psoriasis which eventually may prevent the development of nail dystrophy and psoriatic arthropathy[28] Table 5 highlights the efficacy of CSA in treatment of nail psoriasis.[29-32]

| Author | Year | Study type | No. of patients | Dose | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mittal et al.[29] (India) | 2018 | 90 fingernails in 17 patients were assigned into 3 groups with 30 nails each | Intra-matricial injections of triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg/mL), methotrexate (25 mg/mL) and CSA (50 mg/mL) | In both triamcinolone acetonide and methotrexate groups, 15 (50%) nails out of 30 showed>75% improvement. In the CSA group, only ten (33%) nails showed>75% improvement. | Intra-matricial methotrexate injection yielded the most improvement with minimum side effects, results being comparable to intra-matricial triamcinolone acetonide injection. CSA was the least effective drug, with the most side effects. | |

| Gümüşel et al.[30] (Turkey) | 2011 | Randomized controlled trial | 37 patients | Treatment with methotrexate (initial dose, 15 mg/week) or CSA (initial dose, 5 mg/kg/day) for 24 weeks. |

The mean percentages of reduction of the NAPSI score after methotrexate and CSA treatments were 43.3% and 37.2%, respectively. | A significant improvement was detected in methotrexate group for the nail matrix findings, and in CSA group for the nail bed findings. |

| Feliciani et al.[31] (Italy) | 2004 | Clinical trial | 54 patients Group A-21 patients Group B-33 patients |

Group A-CSA (3.5 mg/kg/day) for 3 months Group B-CSA with topical calcipotriol cream |

Improvement of the clinical symptoms of nails lesions was seen in 79% patient in group B in comparison to 47% patient in group A | In case of severe nail psoriasis, the use of the combination of topical calcipotriol twice a day with systemic CSA |

| Cannavò et al.[32] (Italy) | 2003 | Prospective randomized placebo-controlled study | 16 patients Group A-8 patients Group B-8 patients |

Group A-70% maize-oil-dissolved oral CSA solution Group B-Maize oil alone |

Group A-3 patients showed complete resolution of nail lesions and 5 patients showed substantial improvement compare to Group B | Topical therapy with oral CSA solution is safe, effective and cosmetically highly acceptable |

CSA: Cyclosporine

Psoriatic arthropathy

Multiple studies have documented the efficacy of CSA either alone or in combination with other Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs).[33] A few of these studies are summarized in in Table 6.[33-40]

| Table 6:Studies on efficacy of CSA in treatment of psoriatic arthropathy. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | Study type | No. of patients | Dose | Duration | Remarks |

| Colombo et al.[34] (Italy) | 2017 | Observational, multicenter study | 238 patients | NA | 12 months | However, taking advantage of the data available from the SYNERGY study, we can conclude from this analysis that CSA in monotherapy confirms its efficacy in cutaneous psoriasis and suggests to be effective also on PsA, at least in this limited subgroup of patients, reducing BASDAI and articular signs and symptoms. |

| Karanikolas et al.[35] (Greece) | 2011 | Prospective, nonrandomized, unblinded clinical trial | 170 patients | 57 patients (CSA- 2.5 to 3.75 mg/kg/day) 58 patients’ adalimumab (40 mg every other week) 55 patients (combination) |

12 months | Combination therapy significantly improved Psoriasis Area and Severity Index-50 response rates beyond adalimumab, but not beyond the effect of CSA monotherapy. |

| Fraser et al.[36] (UK) | 2005 | Randomized, multicenter, double-blinded placebo-controlled trial | Out of 72 patients recruited, 38 were randomized to receive CSA in addition to methotrexate (15 mg/week), and the remaining 34 were given placebo along with methotrexate in the same dose | CSA was started at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg/day, with increments at weeks 4, 8, and 12, increasing by 0.5 mg/kg till a maximum dose of 4 mg/kg/day was obtained (if tolerated by the patient) | 12 months | Significant improvements in the following parameters were observed in the group receiving CSA along with methotrexate, when compared with the group receiving methotrexate alone, respectively: Improvement in swollen joints (11.7% vs. 6.5%) C-reactive protein (17.4% vs. 12.7%) Synovitis (33% vs. 6%) |

| Salvarani et al.[37] (Italy) | 2001 | Case series | 12 patients | 3 mg/kg/day | 6 months | Seven patients had greater than 50% reduction in joint swelling and pain Four patients, the disease had stabilized One patient had to withdraw from the study due to nephrotoxicity |

| Spadaro et al.[38] (Italy) | 1995 | Prospective controlled study | 35 patients | Compare the effectiveness and toxicity of CSA (3 mg/kg/day) versus low dose methotrexate (7.5–15 mg/kg/week) | 12 months | At the end of 6 and 12 months of treatment, symptoms of PsA were reduced in both treatment groups However, the toxicity profile was more in the CSA group with more patient withdrawing from the CSA group (41.2%), when compared with the methotrexate group (27.8%) |

| Steinsson et al.[39] (Iceland) | 1993 | Open-label prospective study | 7 patients | 3.5 mg/kg/day | 6 months | All patients had improvement in joint pain and swelling No relapse was documented |

| Gupta et al.[40] (USA) | 1989 | Prospective study | 6 patients | 6 mg/kg/day | 8 weeks | Significant improvement in joint strength, mean grip strength, and activity level However, within 2 weeks of discontinuing of the drug, symptoms recurred |

CSA: Cyclosporine, PsA: Psoriatic arthritis, BASDAI: Bath ankylosing spondylitis activity index

Comparison with other biologics

Numerous agents (TNF-α inhibitors, Anti-IL-12/23, IL-17) have been implicated as targeted therapy for psoriasis. Notably, biological agents are not the first-line drugs and they should be used when the conventional drugs cannot be used or failed. According to the available data, CSA is preferred as first-line therapy because of its rapid onset of action, better efficacy and tolerability, low cost of therapy, and reversible adverse effects in comparison to biological agents. Re-activation of tuberculosis along with other infections and long pre-workup before initiation of the therapy is also a primary concern during therapy making biological agents inferior to CSA therapy.[41]

Allergic disorders

Urticaria

Chronic urticaria is clinically marked by frequently recurring wheals and/or angioedema that are persistent or occur episodically for at least 6 weeks.[42] CSA has been recommended in those cases of chronic spontaneous urticaria as well as in chronic inducible urticaria, which have been unresponsive even after the four-fold escalation of the dose of second-generation antihistaminic agents[43]. Inhibition of basophil activity and mast cell degranulation has also been observed by CSA.[44] Table 7 highlights the studies on efficacy of CSA in treatment of urticaria.[45-57]

| Author | Year | Type of study | No. of patients | Age | Dose and duration | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sehgal et al.[45] (India) | 2024 | Randomized clinical trial | 43 patients 26 female and 17 male patients |

Mean age=29.05±10.19 years | 4–5 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks | Higher doses of CSA (4–5 mg/kg/day) demonstrated better efficacy in controlling symptoms. Majority of the patients did not experience any symptoms at the higher doses (4–5 mg/kg/day) while approximately one-quarter of patients (23.26%) experienced symptom reappearance at lower doses (1–3 mg/kg/day) albeit with reduced severity and frequency. | In this study, CSA has shown significant effectiveness in controlling disease activity in CSU within a short period (3–5 days). We believe that initiating treatment with higher doses of CSA can be safely employed as a short-term therapy for patients with refractory CSU. |

| Chang et al.[46] | 2021 | Retrospective study | 24 patients | 9 to 18 years | 3 mg/kg/day for 10 weeks to 17 months |

Complete control of urticaria symptoms was reported in all 24 patients with a range of 2 days to 3 months. It was reported that more than half of the patients experienced complete control within 2 weeks. Time to relapse after discontinuation of the treatment was reported in 9 out of 24 patients with a range of 1 week to 37 months. |

CSA was efficient and well tolerated in management of pediatric CSU. |

| Kulthanan et al.[47] (Thailand) | 2018 | Meta-analysis Systemic review |

909 patients | More than 18 years | Very low (<2 mg/kg/day), low (from 2 to<4 mg/kg/day), and moderate (4–5 mg/kg/day) doses of CSA for up to 12 weeks | After 4 weeks, the mean relative change in urticaria activity score of CSA-treated patients was−17.89, whereas that of controls was−2.3. The overall response rate to CSA treatment with low to moderate doses at 4, 8, and 12 weeks was 54%, 66%, and 73%, respectively. No studies of very low-dose CSA evaluated response rates at 4, 8, and 12 weeks. Among patients treated with very low, low, and moderate doses of CSA, 6%, 23%, and 57% experienced 1 or more adverse event, respectively. | CSA is effective at low to moderate doses. Adverse events appear to be dose dependent and occur in more than half the patients treated with moderate doses of CSA. We suggest that the appropriate dosage of CSA for CSU may range from 1 to 5 mg/kg/d, and 3 mg/kg/d is a reasonable starting dose for most patients |

| Neverman et al.[48] (USA) | 2014 | Retrospective study | 46 patients 26 female and 20 male patients |

9–18 years Median, 12.5 years |

3 mg/kg/day in two doses for 2 months to 17 months | All the patients who were antihistamine resistant were treated with CSA; all experienced complete resolution of urticaria at times that ranged from 2 days to 3 months (median, 7 days). Relapses responsive to repeated CSA occurred in 5 of the patients after 1 week to 15 months (median, 6 months). Adverse effects were not seen in these patients. | Data were consistent with efficacy and safety of CSA for CU in children when even high doses of antihistamines are ineffective. |

| Guaragna et al.[49] (Italy) | 2013 | Open sequential study | 21 patients | Adults | 4 mg/kg/day | The results obtained show a reduction in the levels of total IgE and a significant improvement in symptoms; there were no adverse effects. | CSA is an excellent treatment for CU because it reduces the activity of T lymphocytes and reduction of the histamine release from the mast cells and basophils. |

| Di Leo et al.[50] (Italy) | 2011 | Retrospective study | 110 patients 63 female and 47 male patients |

22 to 73 years Median=45.6 years |

3 groups Group A=1–1.5 mg/kg/day Group B=1.6–2 mg/kg/day Group C=2.1–3 mg/kg/day for 6 months |

The mean total symptom severity score decreased by 63% in Group A, 76% in Group B, and 85% in Group C after 6 months. Total disappearance of the symptoms was recorded in 43 patients (39.1%): 7 (28%) of Group A; 12 (37.5%) of Group B and 24 (45%) of Group C. After a mean of 2 months from CSA suspension, 14 patients (11%) had recurrence of symptoms. Minor side effects were noted in 8 patients (7%). | study indicates that low-dose, long-term CSA therapy is efficacious and safe in severe unresponsive CIU. |

| Godse[51] (India) | 2008 | Open trial | 5 patients | 20–50 years Mean age=37.8 years |

3 mg/kg/day for 6 weeks to 5 years |

Average urticaria activity score was 5.4. Within 2 weeks of starting CSA, the score came down to 1.6. The male patient discontinued CSA due to high cost of therapy. Score came down to less than one in all four female patients who continued treatment. Side effects were few | This uncontrolled study has shown that low-dose CSA is effective in treating CIU patients, and can be given safely for 3 months. One study showed that prolonged treatment with CSA is beneficial for maintaining remission in severe cases of CU. |

| Serhat Inaloz et al.[52] (Turkey) | 2008 | Prospective controlled study | 27 patients | Range=17–59 years Mean age=36.18±11.76 years |

2.5 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks | In a total of 19 patients (70.37%), the score reduced by 25% after CSA treatment. Thus, these patients were considered to be in total remission. The reduction of the UAS score after CSA treatment was statistically significant in all patients (P<0.005 | Data of this study demonstrate that CSA therapy is efficient and safe for CIU patients. However, it is necessary to observe long-term CSA treatment in future studies because it may help patients maintain long periods of remissions. |

| Vena et al.[53] (Italy) | 2006 | Randomized controlled trial | 99 patients 16 weeks CSA=31, 8 weeks CSA=33, placebo=35 |

16 weeks CSA=44.0±9.8 years, 8 weeks CSA=37.1±11.3 years, placebo=41.7±11.5 years |

5 mg/kg/day (day 0 to day 13), 4 mg/kg/day (day 14 to day 27), 3 mg/kg/day (from day 28) |

Fewer therapeutic failures occurred with 16-week CSA (n=3) than with placebo (n=11) and 8-week CSA (n=8). After 8 and 16 weeks, symptom scores significantly improved in both CSA groups over with placebo. Two patients discontinued because of hypertension. | CSA in addition to background therapy with cetirizine may be useful in the treatment of CIU. |

| Kessel et al.[54] (Israel) | 2006 | Clinical trial | 6 patients | Mean age=40.8±11.9 years | 2–3 mg/kg/day for a period of 11.6±4 years | Five patients are favorably maintained on CSA treatment and do not require additional therapy. One patient required the addition of 5–10 mg/d prednisone (while continuing CSA 3 mg/kg/d) reducing the severity of urticaria. Two patients complained of mild hirsutism and peripheral neuropathy and one of a very mild diarrhea. | Prolonged treatment with CSA is beneficial for maintaining remission in severe cases of CU. It spares the need for corticosteroids and is accompanied with mild side effects. |

| Baskan et al.[55] (Turkey) | 2004 | Randomized clinical trial | 20 patients | 4 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks or 12 weeks |

The clinical improvement was dramatic in the first month of treatment in both groups. There was no significant difference in the frequency of responses, side effects and the reduction of UAS in either group. | The preliminary results of our study suggest that CSA is clinically effective for CU. The prolonged use of this therapy for more than 1 month provides little benefit in the clinical improvement. | |

| Grattan et al.[56] (UK) | 2000 | Randomized clinical trial | 29 patients (19 active, 10 controls) |

19–72 years Median age=33 years |

4 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks | Mean reduction in UAS between weeks 0 and 4 was 12.7 (95% confidence interval, CI 6.6-18.8) for active and 2.3 (95% CI - 3.3–7.9) for placebo (P=0.005). Seventeen non-responders (seven randomized to active and 10 to placebo) chose open-label CSA and 11 responded after 4 weeks. Six of the eight randomized active drug responders relapsed within 6 weeks. Of the 19 responders to randomized and open-label CSA, five (26%) had not relapsed by the study end-point. | This study shows that CSA is effective for CU and provides further evidence for a role of histamine-releasing autoantibodies in the pathogenesis of this chronic “idiopathic” disease. |

IgE: Immunoglobulin E, CI: Confidence interval, CSU: Chronic spontaneous urticarial, CSA: Cycosporine, CIU: Chronic idiopathic urticarial, CU: Chronic urticaria

Comparison with other biologics

CSA alone has been proven to be effective in controlling the disease activity in adults with chronic urticaria refractory to omalizumab. However, the impact of CSA was limited by reversible adverse effects which were more common with pre-existing medical conditions.[57] Response to omalizumab is slower in comparison to cyclosporine if autologous serum skin test and basophil histamine release assay are positive.

AD

CSA has been used as an off-label drug for AD, though it is not FDA-approved for the same.[58] It is approved for severe AD in Europe, Japan, and Brazil as a short-term therapy in children above 2 years of age and adult patients. The molecule is useful for both, short-term, and long-term usage. However, no clear dosimetry and schedule are provided in the guidelines, although the dosage for psoriasis is usually followed.[59] Owing to the cumulative side effects, long-term therapy is restricted up to 1 year.[60] Patients receiving CSA demonstrate excellent improvement of lesions, reduction of itch, improvement of disease severity scores, and quality of life indices. CSA reduces the number of helper/inducer T-cell lymphocytes in affected and perilesional skin. Moreover, CSA rectifies the altered innervations and expression of neuropeptides, eventually reducing the pruritus in AD. CSA also inhibits mast cell proliferation, thereby suggesting a novel mechanism of CSA in the management of AD. Meta-analysis has shown the possibility of rebound phenomenon during withdrawal is minimal, thus CSA tends to maintain the clinical resolution and prevent relapses.[61] Multiple studies have shown that patients with severe AD improve clinically with CSA; however, the rate of relapse and frequency of adverse events vary from patient to patient.

Comparison with other biologics and small molecules

Dupilumab (anti IL-4/13) and human immunoglobulin G4 both have received approval for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, but there are certain limitations of the corresponding data. Discontinuation of therapy among patients attributed to adverse effects, development of flare-ups and lack of a clearcut end point of therapy, are some of the issues which should be kept in mind, while assessing the data. However, CSA alone has been shown to be effective in controlling the disease activity by decreasing the Eczema Area and Severity Index score. Moreover, the studies have shown that CSA has a lesser tendency to produce adverse effects.[62,63] Table 8 highlights the studies on efficacy of CSA in treatment of atopic dermatitis.[64-88]

| Author | Year | Type of study | No. of patients | Age group | Dose and duration | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van der Rijst et al.[62] (Netherlands) | 2025 | Multicentric cohort study | 362 pts; 216 pts CSA administered, 94 pts: MTX 192 pts: dupilumab | 2-17 years (14.9±3.8 years) | Starting dose 4 mg/kg/day, drug survival rate detected for 1, 2 and 3 year | Drug survival rate for 1 year, 2 year and 3 year is 43.9%, 21.5%, and 10.4% respectively. Discontinuation contributed by ineffectiveness and adverse effects | Drug survival rate is less in relation to MTX and dupilumab, which may reflect effectiveness and safety of CSA |

| Alexander et al.[63] (UK) | 2024 | Prospective observational cohort study | 488 pts, CSA in 57 pts, MTX in 149 pts, Dupilumab in 282 pts | 3–82 years (27.4±15.6 years) | 1.4–5 mg/kg 28 days to 1 year (mean 8 months) |

EASI-50,75 and 90 achieved rapid reduction in CSA than methotrexate. In severe disease, EASI, POEM, PP-NRS reduction is more in CSA than dupilumab and methotrexate | CSA most effective in very severe AD with significant improvement in itch and quality of life |

| Flohr et al.[64] (UK and Ireland) | 2023 | Multicentric parallel group assessor blinded RCT | 103 pts, 52 pts were given CSA and 51 pts were given MTX | 2–16 years (10.34±4.21) | 4 mg/kg for 36 weeks, follow up for more 24 weeks | CSA showed better response in 12 weeks with O-SCORAD mean difference−5.69, in 60 weeks, MTX was better with≥75% SCORAD, EASI, 50, 75 decrease. Post treatment flare more reported in CSA | CSA was superior in achieving rapid clearance, and MTX showed sustained disease control following discontinuation |

| Proenca et al.[65] (Brazil) | 2023 | Retrospective observational study | 16 pts | 5–19 years (11.94±4.37) | 3 mg/kg for 6 months | >30% reduction of SCORAD in 75% pts. No serious side effect (4 hypertrichosis, 3 infection) | CSA well tolerated and well effective in children and adult age group in moderate to severe atopic dermatitis |

| Vyas et al.[66](India) | 2023 | Randomized open label parallel group study | 50 pts, allotted in 1:1 ratio in CSA and apremilast group | 12–65 years of age (35±16.43) | 5 mg/kg for 24 weeks and 12 weeks follow up | Mean percentage change in apremilast was 67.79% and in CSA was 83.06%. Adverse effect encountered 28.57% in apremilast group and 1.74% in CSA group | CSA has better efficacy and favorable safety and drug tolerance profile than apremilast |

| Patro et al.[67](India) | 2020 | Retrospective observational study | 14 pts | 0.5–10 years | 3-4 mg/kg for 4 to 12 weeks | TIS score decreased from 5–9 to 0–1; no serious side effect other than GI intolerance | CSA Can be used safely in recalcitrant atopic dermatitis within therapeutic dose |

| Sarıcaoğlu et al.[68] (Turkey) | 2018 | Retrospective observational study | 43 pts | 6–17 years | 2.5–5 mg/kg with median dose of 3 mg/kg for 3–14 months (4.9±4.24) | 39.5% achieved good response, 23.5% achieved moderate response and 32.5% did not response. Side effects were milder | Low dose CSA is effective and safe for children in severe and recalcitrant atopic dermatitis, while higher dose is required for acute and very severe disease |

| Goujon et al.[69](France) | 2018 | Randomized control trial | 97 pts: Group A (MTX in 50 pts) Group B (CSA in 47 pts) | 32.48±9.40 | 2.5 mg/kg for 8 week, if 50% reduction of SCORAD did not occur, them 5 mg/kg for next 16 weeks |

At week 8, SCORAD 50 reduction was 8% in MTX and 42% in CSA. Treatment related adverse events were more common in CSA group | CSA was superior than MTX in week 8 in case of SCORAD reduction. |

| Hernández- Martín et al.[70](Spain) |

2017 | Retrospective study | 63 pts | 8.4±3.6 years | 4.27±0.61 mg/kg for 4.6 months (mean); range 3-12 months | Good to excellent response (64%). Response better without eosinophilia. Prolonged remission in 20% cases | Efficacious and rapidly acting in children; can provide sustained remission in some pts; drug is well tolerated but strict monitoring required |

| Kim et al.[71] (Korea) | 2016 | Prospective RCT | 60 pts divided into group A (oral CSA+topical therapy) and group B (oral CSA) in 1:1 ratio | Mean 22.63 (group A) and 23.43 (group B) | 4.5 mg/kg initial dose, tapered by 1–1.5 mg/kg; Average 3–6 mg/kg; Duration: Till successful treatment (group A [12.1±5.7 weeks]; group B [16.1±6.1 weeks]) |

85.15% pts achieved successful treatment with oral CSA and topical corticosteroid/calcineurin inhibitor group while in CSA monotherapy it was 58.6%. | Though CSA is effective as monotherapy, but concomitant topical therapy improves the efficacy |

| Van der Schaft et al.[72](Netherlands) | 2015 | Multicentric Retrospective cohort study | 356 pts | 37.6±14.2 years | 2 groups ; one group (195 pts) had initial 3.5–5 mg/kg dose with gradual tapering in 3–6 weeks, another group (160 pts) had≤3.5 mg/kg dose with increased dose in insufficient response; duration 3–2190 days with median of 356 days | Intermediate to high dose is related to increased drug survival, related to ineffectiveness, Reasons for discontinuation was disease controlled (26.4%), Side effects (22.2%), ineffectiveness (16.3%) and both side effect and ineffectiveness (6.2%) of the drug | Older age is associated with decreased drug survival due to side effects and disease control. Discontinuation due to ineffectiveness is less in high dose group |

| Jin et al.[73](South Korea) | 2015 | Placebo controlled double blinded RCT | 43 pts divided into group A (glucosamine and CSA) and group B (CSA and placebo) | 20.03±9.36 years | 2 mg/kg for 8 weeks | Group A significantly reduced SCORAD, chemokine ligand 17 than group B but not IL 31, No increase in adverse events | Low dose CSA and glucosamine combination is beneficial in long term treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. |

| Sibbald et al.[74] (Canada) | 2015 | Retrospective study | 15 pts | 11.2±3.4 years | 2.8±0.6 mg/kg; duration 7–15 months, (10.9±2.7) | 80% responded but 42% encountered relapse, Treatment for longer duration prevented relapse, Adverse event led to discontinuation in 3 pts | Low dose and longer duration of treatment decrease the relapse in atopic dermatitis |

| Garrido Colmenero et al.[75] (Spain) | 2015 | Case series | 5 pts | 1–14 years | 5 mg/kg in weekend (2 days), for 20 weeks | Significant decrease in SCORAD (≤30) with reduction in cumulative dose and serum concentration of CSA | Weekend CSA therapy lead to clinical improvement and less serum concentration of CSA , thus allowing prolonged treatment and preventing relapse |

| El-khalawany et al.[76](Egypt) | 2013 | Multicentric RCT | 40 pts; group A (MTX ,20 pts) group B (CSA , 20 pts) | 10.73±2.21 years | 2.5 mg/kg for 12 weeks | SCORAD reduction in CSA group was more (31.35±8.89) than MTX group (26.25±7.03), Side effects were temporary and milder. | CSA is safe, effective and well tolerated in low dose in severe AD. |

| Kwon et al.[77](South Korea) | 2013 | Crossover pilot study | 10 pts | 22.28±8.6 | 3 mg/kg for 26 weeks | Glucosamine combination decreased mean percentage of SCORAD and IL-4,5 level more than CSA monotherapy | CSA and glucosamine combination is an effective treatment in AD. |

| Beaumont et al.[78](UK) | 2012 | Retrospective observational cohort study | 35 pts | 6–13 years; mean age 8 years | 5 mg/kg/day for 10-32 weeks (mean 20 weeks) | CSA resulted in 91% reduction of SCORAD in infection triggered AD. SCORAD index reduction was only 44% when there is persistence or recurrence of infection | CSA provides better results in infection driven AD than in non-infectious triggers and in case of recurrent infection. |

| Haeck et al.[79](Netherlands) | 2011 | Observer blinded RCT | 55 pts; group A (CSA) and group B (Mycophenolate enteric capsule) | 36.56±12.87 years | 3 mg/kg for 30 weeks | SCORAD and TARC level was higher in group B (mycophenolate) than CSA, after medication withdrawal disease activity was more in CSA | Encapsulated mycophenolate is as effective as CSA, but clinical improvement is rapid in case of CSA |

| Schmitt et al.[80](Germany) | 2010 | Double blinded placebo controlled RCT | 38 pts, one group treated with prednisolone followed by placebo, another group by CSA. | 18–55 years | 2.7–4 mg/kg for 6 weeks with 12 weeks follow up | Stable remission achieved in 6/17 pts in CSA group and 1/21 pts in prednisolone group | CSA is significantly more effective in achieving stable remission in severe atopic eczema than prednisolone |

| Bemanian et al.[81](Iran) | 2005 | RCT | 14 pts, divided into group A: 8 pts in CSA group and 6 pts in IVIg group | 11.91±4.29 years | 4 mg/kg for 13 weeks | Reduction of SCORAD occurred in both group, but continued deceleration noted in CSA group. All side effects of drug were transient | CSA is safe, relatively cheaper, easily available and effective drug than IvIg |

| Pacor et al.[82] (Italy) | 2004 | RCT | 30 pts, divided into topical tacrolimus and CSA group in 1:1 ratio | 13–45 years (26.85±10.29) | 3 mg/kg for 6 weeks | Tacrolimus ointment group reported significantly lower SCORAD than the CSA group, Area under curve (AUC) day (0-42) was lower in tacrolimus than CSA | Both topical tacrolimus and oral CS group showed efficacy, but tacrolimus had faster mode of action |

| Granlund et al.[83] (Finland) | 2001 | Multicentric open label trial | 72 pts divided into 1:1 ratio into group A (UVAB phototherapy) and group B (CSA) | 18–70 years | Maximum 4 mg/kg to minimum 1 mg/kg for 8 weeks |

No difference in quality of life but CSA has significantly more days in remission in 1 year study period | CSA seems to be more effective than UVAB in maintaining remission and reasonably safe |

| Bunikowsky et al.[84](Germany) | 2001 | Open prospective study | 10 pts | 22–106 months | 2.5 mg/kg starting dose, increased stepwise in non-responders to maximum of 5 mg/kg dose | 9/10 pts had SCORAD reduction, 4 pts at 2.5 mg/kg dose, 3 pts at 3.5 mg/kg dose and 2 pts at 5 mg/kg dose, with significant reduction in IFN gamma, IL-2, 4, 13 | Low dose microemulsion improves clinical measures and reduces T cell cytoproduction |

| Pacor et al.[85](Italy) | 2001 | Open uncontrolled study | 15 pts | 35.5 years (median) | 5 mg/kg for 8 weeks | 90% reduction in mean extent score in Likert scale | CSA is effective and safe for treating AD |

| Caproni et al.[86](Italy) | 2000 | Open uncontrolled study | 10 pts | 17–56 years | 5 mg/kg for 6 weeks | CD30 level decreased after treatment (135.7–96.2). ECP level also decreased (57.78–18.69). No significant difference in serum IgE level. | CSA therapy results in clinical improvement along with significant reduction in CD30 and ECP level |

| Harper et al.[87](UK) | 2000 | Retrospective observational study | 40 pts | 2–-16 years (10.05±3.2) | 5 mg/kg one group for 12 weeks and another group with 52 weeks | No significant difference in between groups in SASSAD area disease activity monitoring, but improvement were consistent in continuous arm. No clinically significant changes in mean serum creatinine and blood pressure | More consistent control is achieved with continuous treatment. However, short course therapy was adequate for some pts, so the treatment should be tailored according to patient. |

| Czech et al.[88](Germany) | 2000 | Double blinded RCT | 106 pts | ≥18 years (34±8.93) | Divided into group A (150 mg) and group B (300 mg) for 8 weeks | Symptom score decreased from 59 to 39.3 in group A and 60.7 to 33.2 in group B. Serum creatinine rise 0.6% in group A anf 5.8% in group B | Although 300 mg more effective, 150 mg is preferred due to better renal tolerability. |

ECP: Eosinophil cationic protein, IgE: immunoglobulin E, RCT: Randomized controlled trial, pts: Patients, IL: Interleukin, GI: Gastrointestinal, CSA: Cyclosporine, MTX: Methotrexate, EASI: Eczema area and severity index, SCORAD: Scoring atopic dermatitis, PP-NRS: Peak pruritus numerical rating scale, POEM: Patient oriented eczema score, SASSAD: Six area six sign atopic dermatitis score, RCT: Randomized control trial, TIS score: Three item severity score, AD: Atopic dermatitis, UVAB: Ultraviolet light A and B, SASSAD: Six area, six sign atopic dermatitis severity score, TARC: Thymus and activation regulated chemokine, CD: Cluster differentiation, CS: Corticosteroid

Janus kinase inhibitors (abrocitinib, upadacitinib, and tofacitinib) have been also used in the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD who do not respond to conventional therapies. Very limited data on clinical trials including safety, tolerability, and side effects are available whereas ease of availability, cost of therapy, and better tolerability make CSA superior to other biologic therapies.[89]

Dyshidrotic eczema

In case of severe dyshidrotic eczema, non-responding to first-line treatment, CSA can be an effective therapy. Peterson et al. have shown encouraging improvement of severe chronic vesicular hand eczema by treating with high dose CSA (5 mg/kg/day) initially, followed by maintenance in 2.5 mg/kg/day dose. However, recurrence of lesions has been observed once the drug is discontinued.[90]

Chronic hand dermatitis

Chronic hand dermatitis not responding to conventional therapies may show a good response to CSA. Reitamo and Granlund studied the efficacy of CSA in hand eczema in 7 patients, which showed no improvement at a low dose (1.25 mg/kg), and was effective in 5 out of 7 patients in 2.5–3 mg/kg dose and maintained up to 16 weeks.[91] Kim HL et al. in their retrospective review of 16 cases revealed significant improvement in statistical physician’s global assessment, with relapse on drug withdrawal in some cases. However, there were no severe side effects reported.[92]

Parthenium dermatitis

CSA is an effective and safe therapeutic agent which can be used in cases of air-borne contact dermatitis, with an atopic background. Verma et al. observed 20 patients of parthenium dermatitis with 2.5 mg/kg CSA for 3 months (or up to complete clinical remission) and demonstrated significant improvement within 2–4 weeks of initiation of therapy and complete remission was achieved within 1.5–3 months of therapy in all patients.[93] Lakshmi et al. showed improvement in clinical severity score and decrease in serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) level following CSA therapy in two parthenium dermatitis patients with atopic diathesis[94]

Miscellaneous disorders

Other than the common uses, CSA is used in a myriad of clinical conditions.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

CSA is used in Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) for the prevention of disease progression and formation of new lesions. CSA inhibits the activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and inhibits the secretion of granulosin, perforin, and granzyme, thus arresting apoptosis and subsequent disease progression.[95]

Studies have suggested CSA to be a superior drug to other therapeutic options in the management of SJS-TEN. However, the duration of treatment is not standardized, and the drug is used for a month or till the resolution of skin lesions and re-epithelialization. Table 9 highlights the studies on efficacy of CSA in treatment of SJS-TEN.[96-102]

| Author | Year | Type of study | Number of patients | Dose and duration | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poizeau et al.[96] (France) | 2018 | Retrospective cohort study | 95 (received CSA) 79 patients (only supportive care) | 3 mg/kg/day for 10 days | Outcomes did not significantly favour cyclosporine either by exposed/unexposed method or propensity score method. Acute kidney injury were more in patients receiving CSA (P=0.05). | The study did not find CSA to be significantly superior than supportive care |

| Mohanty et al.[97] (India) | 2017 | Record based, observational study | 28 Patients (19 patients in CSA group and 9 patients in supportive care) | 5 mg/kg/day for 10 days | Stabilization, reepithelialization and recovery time were significantly lower in the CSA group (P<0.001, P=0.007, P=0.01, respectively). The standardized mortality ratio (0.32) 3.3 times lower than the only supportive treatment in CSA group | CSA (5 mg/kg/day) for 10 days may reduce the risk of dying, may fasten the healing of lesions and maylead to early discharge from hospital. |

| Lee et al.[98] (Singapore) | 2017 | Retrospective cohort study | 44 patients (24 patients on CSA and 20 patients on supportive care) | 3 mg/kg for 10 days then 2 mg/kg for 10 days then 1 mg/kg for 10 days | 3 deaths were observed within 7.2 SCORTEN predicted deaths in the CSA treated group, whereas 6 deaths were observed among 5.9 predicted deaths in supportive care group. The standardized mortality ratio of SJS/TEN treated with CSA was 0.42 (95% confidence interval 0.09–1.22). | CSA may improve the survival rate in SJS-TEN patients |

| Kirchhof et al.[99] (Canada) | 2014 | Retrospective cohort study | 64 | 3–7 mg/kg/day (mean) for 3–5 days oral or 7 days IV | Standardized mortality ratio was better in CSA (0.43) than IVIg (1.43) group | CSA may provide better mortality benefit than IVIg. |

| Singh et al.[100] (India) | 2013 | Prospective open study with retrospective comparison | 11 patients treated with CSA compared with 6 patients in corticosteroid | 3 mg/kg/day for 7 days followed by dose tapering by 7 days | Mean duration of re-epithelialization, hospital stay was lower in CSA group than corticosteroid group | CSA has encouraging role in SJS-TEN management by reducing the time period for re-epitheliaization and decreasing the hospital stay |

| Reese et al.[101] (USA) | 2011 | Case series | 4 | Initially 5 mg/kg/day in 2 divided dose, one patient was treated for 5 days, other were tapered over 1 month | All patients showed rapid response | CSA is beneficial for rapid response in SJS-TEN management |

| Valeyrie-Allanore et al.[102](France) | 2010 | Open prospective trial | 29 patients (12=SJS/TEN overlap, 10=SJS, TEN=7) | 3 mg/kg/day for 10 days | No death occurred while prognostic score predicted 2.75 deaths, Mean epidermal detachment remained stable in 62% cases. | Both death rate and progression of epidermal detachment improved with CSA, suggesting its beneficial role in SJS-TEN. |

IVig: Intravenous immunoglobulin, SJS: Stevens–Johnson syndrome, TEN: Toxic epidermal necrolysis, CSA: Cycosporine, SCORTEN: Score of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Pyoderma gangrenosum

CSA as a monotherapy or in combination with corticosteroid shows rapid healing of ulcers in the case of pyoderma gangrenosum. The drug has both immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory action on the disease process. Reduction of inflammation is evident within 24 hours of administration of the drug with maximum benefit seen after 2 weeks. However, long-term treatment with proper monitoring is required, else, the condition tends to recur. Table 10 highlights the studies on efficacy of CSA in treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum.[103-108]

| Author | Year | Study type | No. of patients | Dosage | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shah et al.[103](USA) | 2023 | Case series | 7 patients | 2 CSA 100 mg capsules are mixed with 98 mL of 100% vitamin E oil to form topical formulation and applied daily, till healing | 6 out of 7 patients had decreased pain, size and depth of ulcer within 4 weeks of treatment, with earliest in 10 days, however new satelite lesion tends to develope | Topical CSA can be a cost effective, efficacious in pyoderma gangrenosum as a monotherapy and adjuvant |

| Mason et al.[104](UK) | 2017 | multicentre, parallel-group, observer-blind RCT | 112 patients (CSA in 59 patients and corticosteroid in 53 patients) | 4 mg/kg/day | CSA was found to be cost effective than corticosteroid (net cost: −≤1160; 95% CI−2991 to 672); Quality of life improved more with CSA than corticosteroid (net QALYs: 0•055; 95% CI 0•018–0•093) | CSA is cost effective and provides better outcome in relation to quality of life, especially in larger lesions |

| Ormerod et al.[105](UK) | 2015 | Multicentre, parallel group, observer blind, RCT | 112 patients (CSA in 59 patients and corticosteroid in 53 patients) | 4 mg/kg/day | Mean speed of healing is faster in CSA (−0.21 cm/day) than corticosteroid (−0.14 cm/day) in initial 6 weeks duration. By 6 months, 28/59 patients in CSA group and 25/53 patients in corticosteroid group achieved complete healing | No significant difference in response in between CSA and corticosteroid other than rapid healing in initial stages in CSA. |

| Vidal et al.[106](Spain) | 2004 | Case series | 21 patients | 5 mg/kg | 96% patients had complete remission, however patient had recurrences during treatment discontinuation | CSA showed better efficacy with rapid response and acceptable toxicity |

| Friedman et al.[107](USA) | 2001 | Retrospective chart analysis followed by prospective trial | 11 patients (5 ulcerative colitis, 6 Crohn’s disease) | IV CSA 4 mg/kg for 7–22 days followed by oral CSA 4–7 mg/kg/day | Mean time of response was 4.5 days and mean time of closure was 1.4 months. 9 patients were able to discontinue steroid with 7 patients achieved bowel activity remission. No significant toxicity noted | IV CSA is the treatment of choice for steroid refractory bowel associated pyoderma gangrenosum |

| Elgart et al.[108](USA) | 1991 | Case series | 7 patients | 5–7 mg/kg/day | 6 out of 7 patents responded with 3 cases among them achieved complete remission without any relapse. Side effects minimal, (one patient had reactivation of tuberculosis) | CSA is an useful treatment modality in refractory pyoderma gangrenosum |

CSA: Cyclosporine, CI: Confidence interval, RCT: Randomized controlled trial, QALY: Quality-adjusted life year, IV: Intravenous

Lichen planus

CSA gives good results in severe and refractory cases of lichen planus. Pruritus is shown to lessen within 2 weeks of therapy, and resolution of the lesions is observed within 6 weeks. Studies have shown the efficacy of the drug in generalized lichen planus, hypertrophic lichen planus, and actinic lichen planus, but the highest level of evidence and maximum studies are on oral lichen planus and lichen planopilaris. Tables 11-13 highlights the studies on efficacy of CSA in treatment of lichen planus.[109-119]

| Author | Year | Study type | No. of pts | Dosage | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Georgaki et al.[109](Greece) | 2022 | RCT | 32 divided into two groups (Dexamethasone and CSA) (topical) | 100 mg/mL thrice daily for 4 weeks, topically In swish and spit method | At end of 4 weeks treatment period, both showed significant improvement and decrease in pain and dysphagia. Improvement scoring better with dexamethasone. | CSA is beneficial in reducing symptom and signs in symptomatic OLP, however efficcacy less pronounced than topical dexamethasone |

| Monshi et al.[110](Austria) | 2021 | Open label observational study | 21 pts | CSA mouthrinse (200 mg/twice daily) for 4 weeks | Visual analogue scale, physician’s global assessment and dermatology life quality index decreased significantly after 4 weeks, but relapse occur after treatment discontinuation | Pain, extent of disease, quality of life improved with CSA mouthrinse in earli phase. |

| Thongprasom et al.[111](Thailand) | 2007 | RCT | 13 pts; 6 receiving CSA and 7 receiving triamcinolone acetonide | 100 mg/mL thrice daily | Partial response in 2 cases, no significant difference in response with topical steroid | Topical CSA did not provide significant benefit than topical steroid |

| Yoke et al.[112](Singapore) | 2006 | RCT | 139 pts; CSA: 68 pts and TCS: 71 pts | 100 mg/mL thrice daily for 8 weeks | Pain, burning, reticulation, ulceration are found less responsive to topical CSA than TCS | Topical CSA no more effective than TCS in OLP management |

| Eisen et al.[113](USA) | 1990 | Double blinded clinical trial | 16 pts in 1:1 ratio in topical CSA and vehicle group | 5 mL thrice daily (100 mg/mL) for 8 weeks | CSA group had marked improvement in erythema, erosion, reticulation, pain. Did not encounter any significant side effects | Topical CSA is useful in management of OLP |

LP: Lichen planus, CSA: Cyclosporine, OLP: Oral lichen planus, TCS: Topical corticosteroid, RCT: Randomized controlled trial, pts: Patients

| Author | Year | Study type | No. of patients | Dosage | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatemi Naeini et al.[114](Iran) | 2020 | RCT | 33; 17: CSA 16: MTX |

3–5 mg/kg/day for 6 months | Both have beneficial effects and relatively similar efficacy in decreasing mean LPPAI | Both options are preferable, however authors advised methotrexate as an earlier option |

| Bulbul Baskan and Yazici[115](Turkey) | 2018 | Retrospective study | 16 patients; 6 on CSA and 10 on MTX | 3–5 mg/kg/day | Both have shown similar efficacy, however side effect was less in MTX group | Both CSA and MTX are useful option for LPP, however MTX is better tolerated |

| Mirmirani et al.[116](USA) | 2003 | Case series | 3 patients | 3.5 mg/kg short course | Remission achieved in symptoms in highly symptomatic cases in 3 months and they remain asymptomatic for next 12 months | CSA helps in alleviating symptoms in LPP |

LPP: Lichen planopilaris, CSA: Cyclosporine, MTX: Methotrexate, LPPAI: Lichen planopilaris activity index

| Author | Year | Study type | No. of patients | Dosage | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schwager et al.[117](USA) | 2019 | Retrospective study | 18 out 444 patients were administered CSA | 100–400 mg mean 300 mg) | 10 patients (56%) had moderate response, 6 patients had significant (33%) response, 1 worsened and one 1 patients had no change | CSA is effective in lichen planus but response may be variable |

| Grattan et al.[118](UK) | 1989 | Open uncontrolled study | 4 patients with lichen planus hypertrophicus | 5% W/W CSA IV solution under polyethelene occlusion for a month | Scaling decreased, plaques get thinner, and irritation decreased in two cases. Dermal T helper: suppresor cell ratio decreased | Topical CSA is effective in lichen planus hypertrophicus |

| Ho et al.[119](USA) | 1990 | Case series | 2 patients | 6 mg/kg for 6 months | Rapid response in 4 weeks and complete resolution in 8 weeks, no side effect encountered | CSA has encouraging efficacy and safe in management of generalised lichen planus. |

CSA: Cyclosporine, IV: Intravenous

Alopecia areata

Oral cyclosporine has been shown to decrease the perifollicular lymphocytic infiltration, thereby arresting the progression of the disease and eventually leading to regrowth of hairs. CSA can be useful in long-term treatment due to its steroid-sparing effects. Table 14 highlights the studies on efficacy of CSA in treatment of alopecia areata.[120-126]

| Author | Year | Study type | No. of patients | Dosage | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lai et al.[120](Australia) | 2019 | Double-blind, randomized, placebocontrolled trial | 32 patients, 1:1 ratio in CSA and placebo | 4 mg/kg/day for 3 months | The CSA group had a greater proportion of participants achieving at least a 50% reduction in Severity of alopecia tool score (31.3% vs. 6.3% [P=0.07]) and greater proportion of participants achieving a 1-grade improvement in eyelash (18.8% vs. 0% [P=0.07]) and eyebrow (31.3% vs. 0% [P=0.02]) scale score | CSA is effective in AA, with improvement in severity of alopecia tool along with improvement in eyelashes and eyebrow. |

| Jang et al.[121](Korea) | 2016 | Retrospective comparative study | 88 (CSA 51 patients and Betamethasone 37 cases) | 50–400 mg/day with median 200 mg over 13.2 months (mean) | 54.9% responded in CSA group and 37.8% responded in betamethasone group | Oral CSA is superior than betamethasone pulse ij treatment of AA in respect to efficacy and safety profile |

| Açıkgöz et al.[122](Turkey) | 2013 | Open uncontrolled clinical trial | 25 | 2.5–6 mg/kg/day for 2-12 months | Significant hair growth was seen in 10 (45.4%) patients; among them five patients were with multifocal AA, three patients with alopecia universalis and two patients with alopecia totalis. Patients having more than 4 years duration had poor response to treatment (4/25) | Oral CSA treatment may be a beneficial treatment option for severe AA. In addition to this, disease duration is an important prognostic factor which decreases efficacy of oral CSA treatment |

| Kim et al.[123](South korea) | 2008 | Open uncontrolled clinical trial | 46 | 200 mg twice daily CSA which was reduced by 50 mg weekly, total duration 7–14 weeks | 38 (88.4%) had significant hair regrowth and five (11.6%) were considered to be treatment failures. Nine (23.7%) relapsed during the observation period of 12 months | CSA in combination with methylprednisolone can give significant improvement in severe AA |

| Shaheedi-Dadras et al.[124](Iran) | 2008 | Open uncontrolled clinical trial | 18 patients (12 alopecia universalis and 6 alopecia totalis) | Oral CSA 2.5 mg/kg/day for 5 to 8 months along with IV methylprednisolone 500 mg pulse | Adequate response was noted (≥70%) cases in 6 cases (3 alopecia totalis and 3 universalis). No relapse seen in 8 months follow up | Patients with severe and resistant AA, if properly selected, may benefit from intravenous methylprednisolone pulse-therapy plus oral CSA |

| Ferrando and Grimalt[125](Spain) | 1999 | Open label clinical trial | 15 | 5 mg/kg/day for 6–12 months | Vellus hair regrowth was seen in 12 out of 14 patients | CSA is effective in AA with significant regrowth of hair |

| Shapiro et al.[126](Canada) | 1997 | Open label clinical trial | 8 | 5 mg/kg/day | >75% hair growth achieved in 2 out of 8 patients, however relapse occurred after end ot therapy | CSA effectively grows hair, however elapse is common |

AA: Alopecia areata, CSA: Cyclosporine, IV: Intravenous

Vitiligo

CSA can be an effective therapeutic modality of treatment in both unstable and stable vitiligo patients. It has demonstrated its ability to stabilize rapidly progressive vitiligo as well as repigmentation in vitiligo patches. Table 15 highlights the studies on efficacy of CSA in treatment of vitilligo.[127,128]

| Author | Year | Study type | No. of patients | Dosage | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mehta et al.[127](India) | 2021 | Randomized clinical trial | 50 | Group 1: 2.5 mg of dexamethasone per day for 2 consecutive days each week for a period of 4 months. Group 2: ciclosporine at a dosage of 3 mg/kg/day for the same duration of 4 months. |

After 6 months, 21 patients in Group 1 and 22 patients in Group 2 achieved stability, resulting in a similar efficacy of 84% and 88% respectively. | Both CSA and oral steroid is effective in halting the progression of the disease. |

| Taneja et al.[128](India) | 2019 | Open uncontrolled clinical trial | 18 | 3 mg/kg/day | Out of 18 patients, 11 patients had achieved stabillity and among them 9 patients had repigmentation of lesions. | CSA has demonstrated its effectiveness in both stabilization and repigmentation of vitiligo. |

CSA: Cyclosporine

Prurigo nodularis

CSA is considered a second line of management in prurigo nodularis. Significant reduction of pruritus and clearance of lesion is achieved when administered in a dosage of 3 mg/kg/day to 4.5 mg/kg/day for 24–36 weeks.[129] The drug acts by a similar mechanism as in AD. Frequently, high dosages of 3 mg/kg/day to 4.5 mg/kg/day for 24–36 weeks are required. When CSA dosage is reduced, the prurigo lesions tend to reappear.

Sweet syndrome

Sweet syndrome like other neutrophilic dermatosis can be treated with CSA. It can be used as initial monotherapy, a second-line therapy in steroid-resistant cases, or as a steroid-sparing agent. The dose ranges from 2–4 mg/kg/day to 4 mg/kg/day, with the highest dose being 10 mg/kg/day for the resolution of clinical symptoms in acute presentation with proper monitoring. CSA acts by inhibiting neutrophil chemotaxis, impairing the neutrophil migration and thus reducing inflammation. Van der driesch et al. reported a case of a middle-aged lady, treated with a high dose of CSA (10 mg/kg/day), leading to the resolution of skin lesions and systemic symptoms within 9 days. Subsequently, the dose of CSA was reduced within 21 days, without any clinical recurrence.[130]

Behcet’s disease

CSA decreases the mucocutaneous as well as ocular and arthritis symptoms in patients of Behcet’s disease. However, neurological manifestations have a poor response to CSA. Masuda et al. demonstrated that CSA is superior to colchicine, for treating ocular and mucocutaneous manifestations. However, due to the high dose (10 mg/kg/day), adverse effects were more pronounced in the CSA group than in the colchicine group.[131] Avci et al. demonstrated significant improvement in oral and genital aphthae as well as ocular and arthritic components associated with Behcet’s disease.[132]

Granuloma annulare

Multiple case reports have shown the efficacy of CSA in generalized granuloma annulare suggesting its role in management. Spadino et al. reported good improvement of lesions, in 4 patients with disseminated granuloma annulare, treated with oral CSA at a dose of 4 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks, followed by tapering of dose by 0.5 mg/kg/day biweekly.[133]

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP)

CSA has been found beneficial in PRP, especially in erythrodermic cases. It can be used along with acitretin in type I PRP. Usuki et al. demonstrated that CSA (5 mg/kg/day) gives satisfactory results in clinical resolution of erythema and scaling in erythrodermic PRP.[134]

Polymorphous light eruption (PMLE)

CSA has a prophylactic role in PMLE. Lasa et al. suggested that CSA at a dose of 3–4 mg/kg/day can be administered 1 week before travel to a sunny climate with discontinuation of the drug upon return and thus avoiding flare-up of PMLE.[135]

Chronic actinic dermatitis

Chronic actinic dermatitis cases with poor response or rapid relapse following systemic corticosteroid therapy can be treated with CSA (4–4.5 mg/kg/day). Paquet and Pierard have observed good responses to CSA within 4–12 weeks of therapy.[136]

Hailey–Hailey disease (HHD)

Several case reports have reported the efficacy of CSA in refractory cases, in 3–5 mg/kg/dose. However, there is gradual deterioration during dose tapering. Usmani and Wilson reported a dramatic response with combination therapy of low-dose CSA with acitretin in a recalcitrant case of HHD.[137] Varada et al. reported an improvement in lesions and quality of life in a 52-year-old female after adding CSA in a patient who was in on continuous treatment with acitretin.[138]

Hidradenitis suppurativa

CSA can be used in chronic, debilitating cases of hidradenitis suppurativa, in combination with antibiotics. Anderson et al. in their case series have reported mild-to-moderate improvement in 50% cases out of 18 patients, who were previously treated with other treatment modalities.[139]

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus

CSA is used in the setting of SLE as a concomitant systemic therapy or as a third-line therapy for cutaneous lesions when antimalarials, dapsone, oral prednisolone, or retinoid have already failed. Ogawa et al. in their clinical trial have demonstrated 75% improvement with CSA when other immunosuppresives have failed to achieve resolution. They also showed improvement in lupus nephritis along with maintenance of clinical resolution in the SLE patients.[140] CSA can be combined with steroids or other immunosuppressants, which allows dose downgrading of other immunosuppressants and sparing of steroid side effects.

Dermatomyositis

CSA may be used in treatment-refractory cases where methotrexate, azathioprine, and others have failed to provide clinical resolution. Vencovský et al. have compared CSA with methotrexate and it has shown that methotrexate is more beneficial for myopathy and CSA is more beneficial for interstitial lung disease.[141] The drug has been found to be effective in esophageal disease, pulmonary involvement, and amyopathic dermatomyositis.[142,143]

Systemic sclerosis

CSA has shown antifibrotic effect as well as improvement of digital infarcts in some case reports. However, extra caution needs to be followed while administering CSA in systemic sclerosis otherwise the patient may develop malignant hypertension and scleroderma renal crisis.[144]

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of Ofuji

CSA gives satisfactory results in eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of Ofuji.[145] Fukamachi et al. in a case series of six patients reported 100% efficacy of CSA at 100–150 mg/day/dose for 2–12 weeks without any drug-related adverse events.[146]

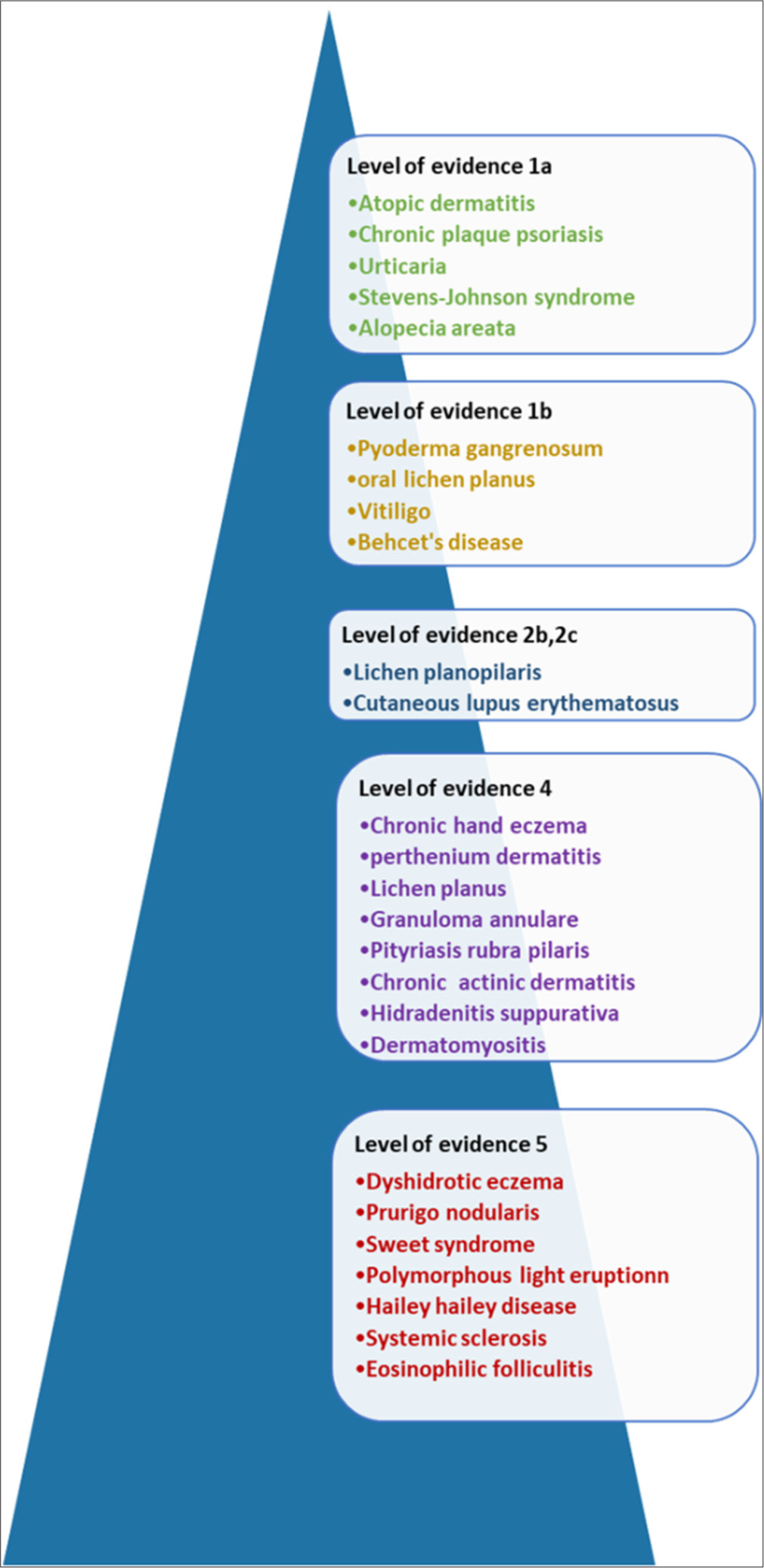

EVIDENCE-BASED REVIEW

The salient features of evidence in support of using cyclosporine is summarised in Table 16 and Figure 2. Level of evidence as per the criteria set by Oxford CEBM (centre of evidence based medicine) is depicted in box 1 [Table 16 and Figure 2].

| Indication of CSA | Level of evidence |

|---|---|

| Atopic dermatitis | 1a |

| Chronic plaque psoriasis | 1a |

| Urticaria | 1a |

| Chronic hand eczema | 4 |

| Dyshidrotic eczema | 5 |

| Perthenium dermatitis | 4 |

| Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis | 1a |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 1b |

| Oral lichen planus | 1b |

| Lichen planopilaris | 2b |

| Lichen planus | 4 |

| Alopecia areata | 1a |

| Vitiligo | 1b |

| Prurigo nodularis | 5 |

| Sweet syndrome | 5 |

| Behcet’s disease | 1b |

| Granuloma annulare | 4 |

| Pityriasis rubra pilaris | 4 |

| Polymorphous light eruption | 5 |

| Chronic actinic dermatitis | 4 |

| Hailey Hailey disease | 5 |

| Hidradenitis suppurativa | 4 |

| Cutaneous lupus erythematosus | 2c |

| Dermatomyositis | 4 |

| Systemic sclerosis | 5 |

| Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of ofuji | 5 |

CEBM: Centre for evidence-based medicine, CSA: Cyclosporine

- Figure depicting the level of evidence of cyclosporin in dermatological indications.

| 1a=Systematic reviews (with homogeneity) of RCTs. |

| 1b=Individual RCT (with narrow confidence interval). |

| 1c=All or none. Met when all patients died before the Rx became available, but some now survive on it; or when some patients died before the Rx became available, but none now die on it. |

| 2a=SR (with homogeneity) of cohort studies. |

| 2b=Individual cohort study (including low quality RCT; e.g., <80% follow-up. |

| 2c=“Outcomes” research; Ecological studies. |

| 3a=SR (with homogeneity) of case-control studies. |

| 3b=Individual case-control study. |

| 4=Case-series (and poor quality cohort and case-control studies) |

| 5=Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or “first principles” |

RCT: Randomized controlled trial, CEBM: Centre for evidence-based medicine, SR: Systematic review, Rx: Treatment

CSA CONGENERS

CSA as a systemic drug in dermatological indications has been used for long with satisfying results. Other than CSA, the drugs that act by a similar mechanism of immunomodulation are oral tacrolimus and recently, oral voclosporin. Drugs in this group have been used in organ transplant recipients with success and with favorable side effect profile. Although not approved for dermatological conditions, the drugs have been used in a number of dermatologic conditions as off-label drugs.

Systemic tacrolimus

Oral tacrolimus was approved by FDA in 1994, for preventing liver transplant rejection.[147] It inhibits calcineurin phosphatase in T lymphocytes and thus prevents transcription of IL-2, similar to CSA, but it is 100 times more potent than CSA. Common side effects are comparable to CSA; however, nephrotoxicity and cardiovascular risk profile have been found better in oral tacrolimus.[148] Oral tacrolimus at a dose of 0.05–0.6 mg/kg/day has been found efficacious in psoriasis, eczema, and urticaria.

Voclosporin

Voclosporin is the most recent calcineurin inhibitor and was FDA-approved for lupus nephritis in 2021. Pharmacokinetic properties have shown voclosporin (0.4–1.5 mg/kg/day) to be more potent than CSA. The side effect profile is more or less similar to CSA and its use in dermatology till now has been limited to psoriasis.[149] Table 17 highlights the comparison of cyclosporine with its congeners.[150-152]

| Property | CSA | Tacrolimus | Voclosporin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potency | Supresses T cell activation | 100 times more potent than CSA | 4 times more potent than CSA |

| Indication | Approved for psoriasis, other indications [Table 1] | Off label use in psoriasis, eczema, urticaria, pyoderma gangrenosum, Behcet’s disease, and graft versus host disease | FDA approved for lupus nephritis, Off label use in Psoriasis |

| Dosage | 3–5 mg/kg/day | 0.05–0.6 mg/kg/day | 0.4–1.5 mg/kg/day |

| Absorption and bioavailability | Variable | Better, so it is preferable in inflammatory bowel disease associated pyoderma gangrenosum.[150] | Better bioavailability than CSA |