Translate this page into:

Atopic dermatitis in teenagers and adults: Clinical features of a tertiary referral hospital

*Corresponding author: Larissa Starling, Department of Immunology, Universidade Federal Do Rio De Janeiro (UFRJ), Rua Rodolpho Paulo Rocco, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. starling_larissa@hotmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Starling L, Dortas Junior SD, Lupi O, Valle S. Atopic dermatitis in teenagers and adults: Clinical features of a tertiary referral hospital. Indian J Skin Allergy 2023;2:81-5.

Abstract

Objectives:

This study based on an epidemiological registry aimed to characterize the clinical, epidemiological presentation and impact of atopic dermatitis on the quality of life (QoL) of teenagers and adult patients treated at the outpatient clinic of Atopic Tertiary Referral Hospital in Brazil.

Material and Methods:

Ambidirectional study, with prospective and retrospective data collection of patients, aged ≥13 years, diagnosed with AD. Sociodemographic, clinical information, and immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels were obtained using a specific protocol, as well as assessment of QoL using the psychosomatic scale for atopic dermatitis (AD) (PSS-AD) questionnaire.

Results:

Seventy patients were enrolled, 43 (61.4%) were female and 54 (77.1%) were ≥18 year. The mean age of AD patients was 29.2 years (standard deviation ± 15.5). Most AD symptom associates were itching (100%) followed by insomnia (74.3%). Emotional distress was the most frequently self-reported AD triggering factor (90%). With this study, we have demonstrated that AD type 2 inflammation (97.1%) was most common, which is characterized by high IgE levels. Moreover, 44.3% and 45.7% of patients evaluated by the scoring atopic dermatitis index score, had severe and moderate disease respectively. The PSS-AD questionnaire showed negative mental health impact in AD patients.

Conclusion:

Adults and teenagers (≥ 13 years) with persistent AD need global management, including psychological and mental health support.

Keywords

Atopic dermatitis

Epidemiologic study

Quality of life impacts

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD), is a chronic, relapsing skin disease that causes inflammation, redness and itching. It usually begins in childhood, and flare-ups can continue through adulthood. Symptoms and clinical features are xerosis, eczematous lesions, and pruritus especially at night that contributes to insomnia and impaired mental health. Atopic march often begins with AD, and progresses to have concomitant atopic diseases, such as asthma, food allergy, and allergic rhinitis (AR). Recent evidence about pathophysiology suggests that it is a systemic disorder, characterized by interactions between skin barrier defects and immune dysregulation.[1-3]

Data from the World Health Organization Global Burden of Diseases initiative indicates that at least 230 million people worldwide have AD, and AD is the leading cause of disease burden of non- fatal skin conditions.[1,4,5]

AD affects not only patients but also their families too. A robust multidimensional burden has been described that includes not only the skin symptoms associated with AD, but also depression, anxiety, conduct disorder, and autism, and this relationship is further exacerbated by sleep disturbances and disease severity and reductions in quality of life (QoL) and work productivity.[6-10] Therefore, AD QoL impacts are higher with AD severity.[1,3,10-14] It is important to understand the clinical course and how to improve the management of AD in adults, especially those with refractory types of the disease. Besides, Brazil lacks comprehensive characterization of AD in adults.[3-10]

Based on the epidemiological registry, this study is aimed to characterize the clinical presentation, and evaluate the impact on QoL in AD teenagers and adult patients treated at the outpatient clinic of the Atopic Tertiary Referral Hospital in Brazil.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Data source

Following the approval by Clementino Fraga Filho (HUCFFUFRJ) University Hospital – Rio de Janeiro Medical Ethics Committee (CAAE 20028319.0.0000.5257), we carried out this ambidirectional study with prospective and retrospective data collection of characteristics, epidemiological data and impact on QoL in AD patients, including teenagers and adults at Tertiary Referral University Hospital.

Our study was performed from April 2017 to April 2020, at the AD Clinical Care at Tertiary Referral University Hospital. The inclusion criteria were AD patients treated at Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital, aged over 13 years.

After signing the informed consent including the assent proforma for, and the informed consent for the legal guardian, data was collected according to an attendance form adopted by the service, in which information on demographic (age, sex), academic education, place of birth, family and personal history of atopy (AR, AD, asthma) admission for AD, triggering factors, associated symptoms, minor criteria for AD (Dennie-Morgan double-fold, pityriasis alba, Hertoghe’s sign, xerosis, chronic nonspecific dermatitis of hands and feet, periorbital darkening, periorbital eczema, white dermographism, facial pallor, nipple eczema, keratosis pilaris, alopecia areata, cholinergic urticaria, palmar hyperlinearity) and characteristics such as, age at onset and lesion morphology, and also AD severity by evaluating the scoring atopic dermatitis index (SCORAD) score. It was assessed at the first visit and 3 months later.

Besides, patients were classified as “intrinsic” or “extrinsic” AD according to serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels.[11]

AD health-related quality was assessed using the psychosomatic scale for AD (PSS-AD) that analyzes dimension (stress/laziness/insecurity) and dimension II (non-conformity/relationships).[14] Assessment of psychological impact of the disease using PSS-AD was grouped as “very little + little” and “a lot + extremely”

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed, presented in the form of tables and graphs of the observed data, and expressed by frequency (n) and percentage (%). Age was expressed as mean and standard deviation in addition to minimum and maximum values.

The inferential analysis consisted of the McNemar test to verify whether there was a significant variation in the SCORAD from before and after treatment. The data collected were grouped into plain Microsoft Excel® spreadsheets and subsequently converted into software SPSS version 26 to perform statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Seventy patients were enrolled. Forty-three (61.4%) were female and 54 (77.1%) were ≥ 18 years [Table 1]. Mean age at enrollment was 29.2 (±15.5) years, ranging from 13 to 74 years [Table 1].

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age ≥18 years old | ||

| Yes | 54 | 77.1 |

| No | 16 | 22.9 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 27 | 38.6 |

| Male | 43 | 61.4 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Illiterate | 1 | 1.4 |

| Fundamental | 14 | 20.0 |

| Average | 41 | 58.6 |

| Higher | 14 | 20.0 |

| Region | ||

| Metropolitan | 59 | 84.3 |

| Middle Paraíba | 8 | 11.4 |

| Lakes | 3 | 4.3 |

| Comorbidity | ||

| Asthma | 31 | 44.3 |

| AR | 39 | 55.7 |

| Keratoconus | 3 | 4.3 |

| Family history | ||

| AD | 14 | 20.0 |

| AR | 24 | 34.3 |

| Asthma | 19 | 27.1 |

| Symptom | ||

| Itching | 70 | 100.0 |

| Insomnia | 52 | 74.3 |

| High total IgE | ||

| Yes | 65 | 97.1 |

IgE: Immunoglobulin E, AD: Atopic dermatitis, AR: Allergic rhinitis

We summarized sociodemographic characteristics, atopy comorbidities, atopy family history, and IgE level of the patients analyzed in [Table 1]. IgE levels higher than >150 IU/mL was seen in 68 (97.1%), while 2 (2.9%) had low levels. Therefore, results suggested that type 2 immune pathway activation was most prevalent.

Fourteen subjects (20%) had family history of AD, 24 (34.3%) of AR, and 19 (27.1%) of asthma. Regarding personal history, 39 patients (55.7%) had AR and 31 (44.3%) presented with asthma. The most common symptoms were itching (100%) and insomnia (74.3%) [Table 1].

In our study, 30% of patients had a history of hospitalization due to AD [Table 2].

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital admission by AD | ||

| Yes | 21 | 30.0 |

| No | 49 | 70.0 |

| Dennie Morgan Fold | ||

| Yes | 27 | 38.6 |

| No | 43 | 61.4 |

| Pityriasis alba | ||

| Yes | 15 | 21.4 |

| No | 55 | 78.6 |

| Hertoghe sign | ||

| Yes | 4 | 5.7 |

| No | 66 | 94.3 |

| Xerosis | ||

| Yes | 64 | 91.4 |

| No | 6 | 8.6 |

| Hand and feet eczema | ||

| Yes | 18 | 25.7 |

| No | 52 | 74.3 |

| Dark circles | ||

| Yes | 55 | 78.6 |

| No | 15 | 21.4 |

| Periorbital eczema | ||

| Yes | 40 | 57.1 |

| No | 30 | 42.9 |

| White dermographism | ||

| Yes | 6 | 8.6 |

| No | 64 | 91.4 |

AD: Atopic dermatitis

Lichenification was seen in 46 (65.7%) patients. According to Hanifin and Rajka minor criteria of AD, xerosis (91.4%) followed by periorbital dark circles (78.6%) were more prevalent [Table 2]. Triggers like emotional distress and weather change was seen in 63 (90%) and 58 (82.9%) patients respectively [Table 3].

| Answer | Variable | |||||||||||

| Climate | Environment | Mold | Tobacco | Cat | Dog | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Yes | 58 | 82.9 | 18 | 25.7 | 33 | 47.1 | 33 | 47.1 | 19 | 27.1 | 17 | 24.3 |

| No | 12 | 17.1 | 52 | 74.3 | 37 | 52.9 | 37 | 52.9 | 51 | 72.9 | 53 | 75.7 |

| Answer | Egg white | Wheat | Cow milk | Peanut | Emotional stress | Physical stress: Exercise | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Yes | 6 | 8.6 | 2 | 2.9 | 9 | 12.9 | 2 | 2.9 | 63 | 90.0 | 39 | 55.7 |

| No | 64 | 91.4 | 68 | 97.1 | 61 | 87.1 | 68 | 97.1 | 7 | 10.0 | 31 | 44.3 |

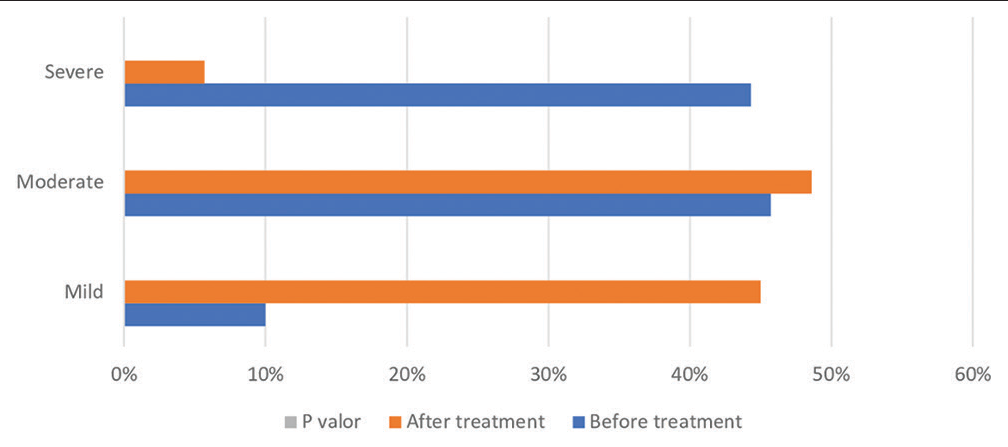

To analyze Qol impacts, a PSS-AD questionnaire was administered and the question with the highest average score was 4, “Itching increases when I get nervous,” preceded by question 1, “Skin allergy worsens with stress”[Table 4]. Thus, we observed that stress plays an important role as a possible trigger. AD severity using SCORAD was analyzed before and after treatment, as shown in [Table 4]. Amongst the 32 patients diagnosed with moderate AD at baseline, 18 changed to mild and 14 continued to have moderate disease in the post-treatment evaluation. Out of the 31 patients with pre-treatment severe AD, 7 became mild, 20 moderate and 4 continued to have severe disease post-treatment. It was observed that there was a significant variation in SCORAD from pre- to post-treatment (P < 0.001), with an improvement of 45 patients (64.3%) and no change in 25 patients (35.7%) [Figure 1].

| Answer | Question 1 | Question 2 | Question 3 | Question 4 | Question 5 | Question 6 | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Nothing (0) | 3 | 4.3 | 5 | 7.1 | 18 | 25.7 | 5 | 7.1 | 20 | 28.6 | 13 | 18.6 |

| Very little + little (1+2) | 11 | 15.7 | 17 | 24.3 | 18 | 25.7 | 8 | 11.4 | 17 | 24.3 | 19 | 27.1 |

| Medium (3) | 18 | 25.7 | 24 | 34.3 | 19 | 27.1 | 18 | 25.7 | 17 | 24.3 | 23 | 32.9 |

| Very + Extremely (4+5) | 38 | 54.3 | 24 | 34.3 | 15 | 21.4 | 39 | 55.7 | 16 | 22.9 | 15 | 21.4 |

| Answer | Question 7 | Question 8 | Question 9 | Question 10 | Question 11 | Question 12 | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Nothing (0) | 7 | 10 | 21 | 30 | 9 | 12.9 | 15 | 21.4 | 14 | 20 | 10 | 14.3 |

| Very little + little (1+2) | 22 | 31.4 | 19 | 27.1 | 11 | 15.7 | 16 | 22.9 | 22 | 31.4 | 12 | 17.1 |

| Medium (3) | 22 | 31.4 | 18 | 25.7 | 22 | 31.4 | 21 | 30 | 19 | 27.1 | 26 | 37.1 |

| Very + Extremely (4+5) | 19 | 27.1 | 12 | 17.1 | 28 | 40 | 18 | 25.7 | 15 | 21.4 | 22 | 31.4 |

PSS-AD: Psychosomatic scale for atopic dermatitis. PSS-AD questionnaire: 01. The skin allergy worsens with stress. 02. The allergy makes me feel too lazy to do anything. 03. I don’t understand why I’m not getting better despite the treatment. 04. The itching increases when I get nervous. 05. I feel that I don’t have good relationships with other people because of the allergy. 06. I don’t understand why the skin allergy gets worse all the time. 07. I scratch my skin because I feel insecure and nervous. 08. I don’t understand why I’m the only one who suffers from this disease. 09. The itching appears when I’m angry, nervous or sad. 10. I feel that I won’t be able to do anything until the allergy gets better. 11. I did everything the doctor told me to, but I can’t see any results. 12. I’m worried about other people looking at me, because of my disease.

- Scoring atopic dermatitis index before and after treatment of the total sample.

DISCUSSION

AD patients frequently suffer from intense flare-ups due to uncontrolled and chronic disease.[15,16] Many worldwide studies have shown impact of AD on work absenteeism, daily activities, and mental health.[17-20] Therefore, optimization of both patient follow-up and disease course must become a priority for AD patients.

The overall sex ratio amongst this sample favored female and the mean age was 29.2 (±15.5) years, ranging from 13 to 74 years. These characteristics were similar to worldwide studies that show AD prevalence to be higher in the age group of 25–44 years, which may reflect the persistence of AD throughout life with periods of relapses and remissions.[15-22] This increased prevalence in females, since puberty is also seen in other atopic disorders.[18] Estradiol and other sex hormones exacerbate T helper 2 inflammation in AD patients.[16-22]

In our study population, we also observed that 75.6% of patients reported symptom onset in the pediatric age group, while 24.3% had the adult age group (20 years or older) onset of symptoms. Similarly, in a meta-analysis, 26.1% of adults with AD reported adult onset of the disease.[20-23]

The age at diagnosis was higher in the age group of 20-29 years and 5-9 years (17.1% each). The low rate of AD clearance in the latter group reflects a possible difficulty in accessing public services, delaying early diagnosis, and morbidity. Besides, data on elderly patients are largely scarce. In our research, we had elderly patients but they did not report symptoms after 60 years. Although their presence and persistence shows a chronic relapsing-remitting nature, which demonstrates AD prevalence in elderly patients too.[24-27]

When the adult reports onset of AD at this stage, it may be a bias of forgetting the relapse of AD in childhood. Besides, it is possible that some cases of adult-onset AD are adult-recurrent AD, rather than adult-onset AD.[28-31]

Around 55.7% of the patients showed personal history of AR, which was observed as the most common atopic manifestation associated with AD adults.[10,31-33]

Our study showed a lichenified and eczematous pattern in skin lesions. These characteristics have been described as a distinct type in AD adults, but they may have mixed heterogeneous forms characteristic of pediatric AD.[29,30,34]

Regarding the minor criteria in our study, xerosis (91.4%) was more prevalent. It may be associated with a higher frequency of pruritus (100%), which is generally the second most frequent atopic dermatitis criteria.[10,35]

Sleep disturbances are a frequent consequence of itching, and can be associated with mental health issues.[34] In this analysis, the prevalence of insomnia was 74.3%. In addition, itching was worse at night, thus interfering with the quality of sleep.[32,35]

As a trigger factor in our study, emotional stress (90%) has contributed to the relapse of the disease. Although we present more severe cases according to the pre-treatment SCORAD (severe 44.3%; moderate 45.7%), we observed that the majority (70%) had no previous hospitalization that differed from previous studies in literature (49%).[12,35] It should be interpreted with caution, as the study population included patients monitored in a tertiary care environment of the SUS, with constant difficulties in hospitalization.

We found that there is a significant variation in the SCORAD from pre- to post-treatment (P < 0.0001), with an improvement of 45 patients (64.3%) and without change in 25 patients (35.7%), suggesting efficacy in the treatment, especially in cases that were severe and mild pre-treatment period.

Our results also showed that, in the pre-treatment period, severe cases corresponded to 44.3% and 45.7% moderate, evaluated by the SCORAD score. This high proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe disease should be carefully interpreted, as the study population included patients followed in tertiary referral hospitals, thus presenting a more severe disease type. Differences in AD severity was observed in other studies, in which 289 (weighted prevalence of 53.1%) reported having mild, 172 (38.8%) moderate, and 34 (8.1%) severe AD.[33,35]

In PSS-AD, the question with the highest average score was 4, “Itching increases when I get nervous,” preceded by question 1, “Skin allergy gets worse with stress.” Similarly, in a systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 studies, AD patients had more chance of suicidal ideation, and more chance of a suicide attempt compared with patients without AD.[7,32,35]

Most patients in this study also presented with characteristics of type 2 inflammation, considering the protocol cutoff of IgE levels. Extrinsic or allergic AD shows high total serum IgE levels and the presence of specific IgE for environmental and food allergens, whereas intrinsic or non-allergic AD exhibits normal total IgE values and the absence of specific IgE.[34,35]

CONCLUSION

To manage AD patients, we need to consider global issues, such as associated symptoms, triggers factors, and need for psychological support. With this study, we showed higher prevalence of AD in females and disease persistence in patients aged over 18 years (77.1%). Besides, exacerbation of AD by emotional stress that contributed to the causation of a higher quality of life impairment.

Our results can be an important stimulus to research on unmet needs of AD in this age group with a larger sample, and a better understanding of not only ways to treat the disease, but also phenotyping this population. Further studies are necessary to better understand the impact on QoL, pathogenesis, and optimal treatment approaches in adult-onset or recurrent AD.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: Results from an international survey. Allergy. 2018;73:1284-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atopic dermatitis in adults: Clinical and epidemiological considerations. Rev Assoc Médica Bras (1992). 2013;59:270-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Profile of patients admitted to a triage dermatology clinic at a tertiary hospital in São Paulo, Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:318-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adult eczema in Italy: Prevalence and associations with environmental factors. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1180-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of atopic dermatitis severity over time. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:349-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association between atopic dermatitis and suicidality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:178-87.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social isolation, loneliness and depression in Young adulthood: A behavioural genetic analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:339-48.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atopic dermatitis epidemiology and unmet need in the United Kingdom. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:801-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Italian multicentre study on adult atopic dermatitis: Persistent versus adult-onset disease. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:443-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact on the quality of life of dermatological patients in southern Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1113-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical features and disease management in adult patients with atopic dermatitis receiving care at reference hospitals in Brazil: The ADAPT Study. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2021;31:236-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A population-based survey of eczema prevalence in the United States. Dermatitis. 2007;18:82-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Translation and validation into Portuguese of a questionnaire for assessment of psychosomatic symptoms in adults with atopic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:764-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of adult atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:595-605.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of atopic dermatitis beyond childhood: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Allergy. 2018;73:696-704.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1251-8.e23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Influence of childhood atopic dermatitis on health of mothers, and its impact on Asian families. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21:501-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment in adults with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2018;29:270-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: A population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:340-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic implications of sex differences in asthma and atopy. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:587-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How epidemiology has challenged 3 prevailing concepts about atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;1108:209-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adult-onset atopic dermatitis: Characteristics and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:771-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and phenotype of adult-onset atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;80:1526-32.e7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persistence of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:593-600.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of parental eczema, hayfever, and asthma with atopic dermatitis in infancy: Birth cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:917-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of polymorphisms in the filaggrin 2 gene in patients with atopic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:173-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atopic dermatitis in adults: A diagnostic challenge. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2017;27:78-88.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comorbidities and the impact of atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:144-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atopic dermatitis from adolescence to adulthood in the TOACS cohort: Prevalence, persistence and comorbidities. Allergy. 2015;70:836-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleep disturbance and atopic dermatitis: A bidirectional relationship? Med Hypotheses. 2020;140:109637.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient burden of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD): Insights from a phase 2b clinical trial of dupilumab in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:491-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical relevance of eosinophils, basophils, serum total IgE level, allergen-specific IgE, and clinical features in atopic dermatitis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34:e23214.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Determinants of treatment goals and satisfaction of patients with atopic eczema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:458-65.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]