Translate this page into:

The impact of hand eczema severity on quality of life in workers engaged in lock making: A cross-sectional study from tertiary care hospital

*Corresponding author: Moin Ahmad Siddiqui, Department of Dermatology, Integral Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India. moinahmad12@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Siddiqui MA, Sarshar F, Saraswat A. The impact of hand eczema severity on quality of life in workers engaged in lock making: A cross-sectional study from tertiary care hospital. Indian J Skin Allergy 2023;2:18-24.

Abstract

Objectives:

Hand eczema is a frequent condition that dermatologists commonly encounter. It leads to considerable impact on quality of life (QOL) by significant functional impairment, disruption of work, and discomfort in the working population. The symptoms range from a minor discomfort to a serious debilitating and long-term conditions. Workers engaged in lock making constitute an economically poor section of society. They are exposed to different kinds of allergens, hence are predisposed to develop hand eczema. The aim of this study was to study the impact of hand eczema on the QOL in workers engaged in lock making.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 65 workers engaged in lock making and suffering from hand eczema, who visited the out-patient department of dermatology for 6 months, were included in this study. Data on QOL were obtained through a questionnaire devised by Finlay et al. Hand eczema severity index (HECSI) was used to assess the severity of disease. Associations were drawn regarding Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and HECSI scores with age, sex, duration of disease, number of episodes of illness, and number of sick leaves.

Results:

Sixty-five patients suffering from hand eczema and engaged in lock making participated in this study, of which 52 (80%) were male and 13 (20%) were female. The commonest age group affected was 36–40 years (41.53%). The most common morphological pattern seen was hyperkeratotic palmar eczema in 50.7% (n = 33) patients followed by chronic dry fissured eczema in 35.3% (n = 23). The mean HECSI score was 19.52 (Standard deviation [SD] = 9.416) and mean DLQI score was 9.92 (SD = 2.426). A significant association of DLQI was seen with duration of disease (P = 0.011), number of episodes of eczema (P = 0.003), and number of sick leaves taken (P = 0.005). Similarly, HECSI score showed significant association with duration of disease (P = 0.002) but not with number of episodes of eczema (P = 0.056). No significant association was found between hand eczema severity and QOL. Being a OPD-based study, it may not truly reflect the community data. Patch test could not be done as workers were poor and could not afford it.

Conclusion:

Lock makers with hand eczema showed considerable impairment of their QOL. Further, they are more prone to absenteeism from work.

Keywords

Hand eczema

Lock makers

Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Hand eczema is a severe, chronic and debilitating disease characterized by papules, vesicles, edema, erythema, scaling, crusting, fissuring and hyperkeratosis, as well as itching and pain.[1] Subjective symptoms include pain and itching. These lead to sleep disturbances, avoidance of social activities, and other activities that require active hand usage.[2] Symptoms that contribute to unfavorable esthetic changes include redness, vesicles, scaling, and hyperkeratosis. In extreme circumstances, they can lead to embarrassment, social isolation and depression. Normal family life is disrupted, including caretaking of children. Employment status may be affected. Patients who have hand eczema caused or exacerbated by work related exposures may need to change occupations or modify their work habits to decrease the strain on their skin. Hand eczema is seen as an expensive disease due to treatment cost as well as indirect expenditure associated with missed working hours.[3,4]

Because occupational exposures induce or worsen hand eczema, the cost of compensation and rehabilitation to workers is enormous. In contrast to other occupational illnesses, it frequently affects young individuals who are juggling a work, a career, and small children, further increasing the burden and societal costs associated with the condition.

Occupational hand eczema refers to contact dermatitis on the hands caused or worsened by occupational exposure. The bulk of all notifiable skin diseases is caused by occupational hand eczema. The yearly incidence varies between nations due to differences in the law and the ability to receive workers compensation. Occupational hand eczema may result in time off work due to illness, which puts economic burden on society.[3]

Need for assessing quality of life (QOL)

Because hand eczema is chronic, debilitating, and disfiguring, it has a major influence on a patient’s QOL. Because typical biomedical outcome measures may fail to capture these effects on patient, QOL assessment has become an essential objective in clinical practice. Many industrial sectors have made it a regulatory obligation to utilize QOL and other patient-reported outcomes to support labeling claims.[5]

There is a shortage of literature from India analyzing the effects of hand eczema on the life quality and its economic implications. The impact of this disease on certain populations or occupations in India has most likely not been studied. In this study, we assessed the impact of hand eczema on the QOL in workers engaged in lock making in patients attending a tertiary care center in our town famous for lock industry work. We also tried to find the correlation of QOL and hand eczema severity with disease duration, number of episodes of eczema, and number of sick leaves taken.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted on all clinically diagnosed cases of hand eczema attending the outpatient department of dermatology, venereology, and leprosy for 6 months. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee.

All patients who presented with hand lesions suggestive of eczema and engaged in lock making, were included in the study after a written and informed consent. Patients <16 years of age, those with concomitant fungal infection of hand or palmar psoriasis with/without other psoriatic skin lesions and/or nail involvement, and those with any other illness affecting their QOL were excluded from the study.

Patients were enquired regarding their demographic profile, disease duration, number of episodes, and sick leaves taken. The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was used to collect data on QOL using a questionnaire.[6] The DLQI consists of ten questions that address six domains of daily life encountered in the past 1 week: Symptoms and feelings, leisure items, daily activities, personal relationships, work and school, and treatment. Each item was graded on a four-point scale: Not at all/not relevant, a little, a lot, and very much. The DLQI score was determined by adding the scores of each question (maximum score – 30 and minimum – 0). Higher was the score, greater the impairment of life quality. The effect on life was graded using DLQI scores using Hongbo et al.[7] classification as: No effect (DLQI score of 1), small effect (DLQI score of 2–5), moderate effect (DLQI score of 6–10), very large effect (DLQI score of 11–20), and extremely large effect (DLQI score of 21–30).

Clinical evaluation was done and severity was assessed by hand eczema severity index (HECSI) score.[8] The HECSI score divides each hand into five areas: Tips of fingers, fingers except the fingertips, palm, dorsum of hand, and wrist. In each of these segments, the affected region is rated as follows: 0: No involvement, 1: 1–25% involvement, 2: 26–50% involvement, 3: 51–75% involvement, and 4: 76–100% involvement. Erythema, induration, papules, vesicles, fissures, scales, and edema are all graded for each location. Each of these morphological symptoms is scored on an intensity scale of 0: no change, 1: mild, 2: moderate, and 3: severe. The sum of the intensity is multiplied by the extent of involvement for each area. The total score for each area is added to calculate the HECSI score. It varies from 0 to 360 points.

Statistical analysis

All the data were analyzed using SPSS software™ version 25.0. Spearman’s rank correlation Chi-square test and independent “t” tests were used for data analysis. Data are being presented in form of charts and tables.

RESULTS

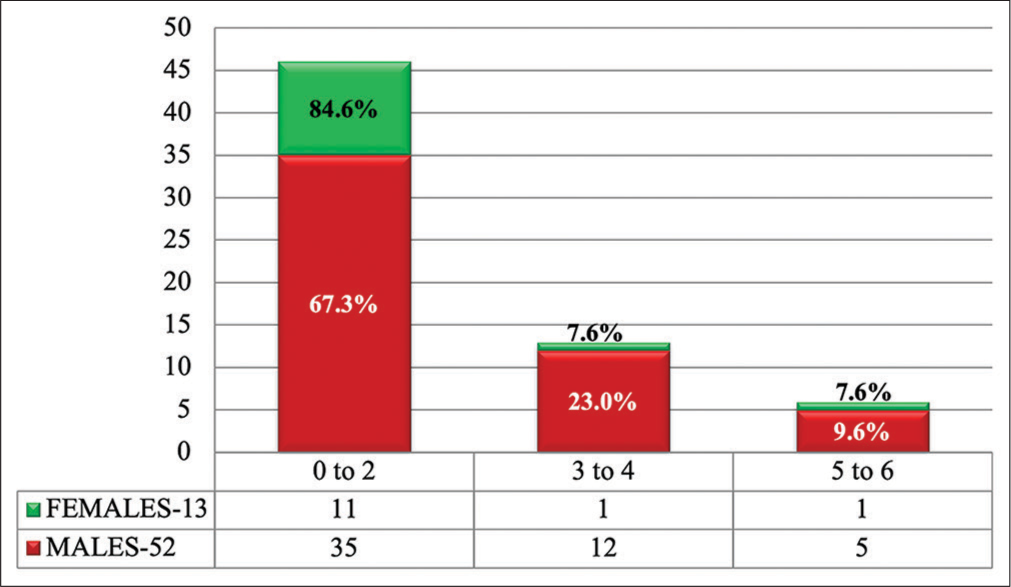

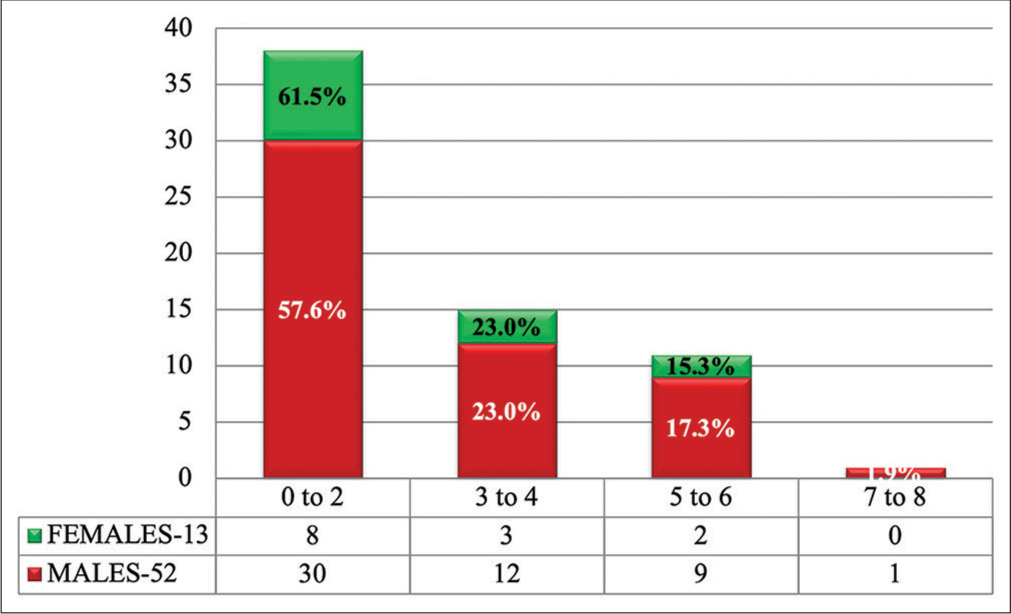

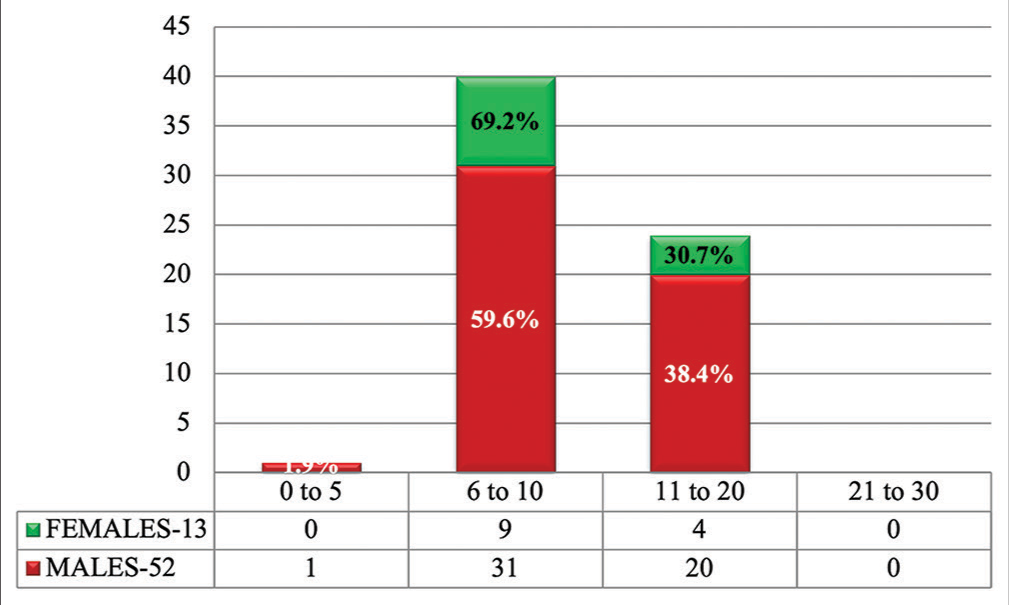

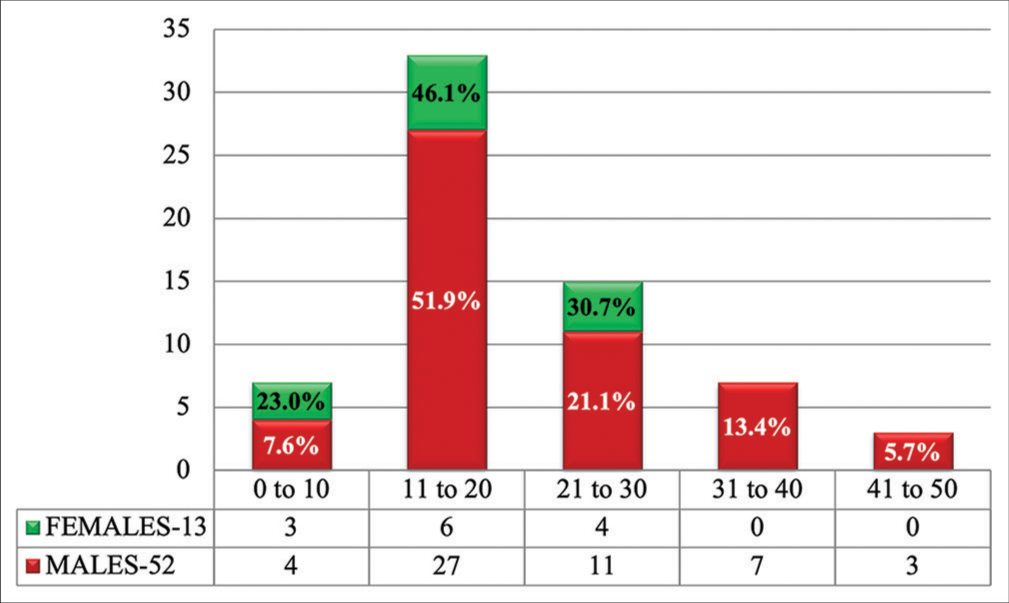

A total of 65 patients participated in the study, of which 52 (80.0%) were male and 13 (20.0%) were female. Most common age group affected was 36–40 years (41.5%). The mean age was found to be 36.65 ± 4.57 years among males and 33.76 ± 4.69 years among females, overall mean age was 36.08 ± 4.71 years. History of atopy was present in 16.9% (n = 11) of patients. The duration of disease in majority of our patients was found to be 0–12 months (n = 44). The epidemiological characteristics of the patients are shown in [Table 1]. The most common morphological pattern seen was hyperkeratotic palmar eczema in 50.7% (n = 33) patients, followed by chronic dry fissured eczema in 35.3% (n = 23), nummular eczema in 7.69% (n = 5), mixed pattern in 4.61% (n = 3), and vesicular eczema with recurrent eruption in 1.53% (n = 1) patients. The mean duration of disease was found to be 10.92 ± 7.41 months. The mean number of sick leaves taken by the patients were 1.82 ± 1.59. More than two-thirds of male patients and more than four-fifths of female patients had to take up to 2 leaves of absence each time they had an episode of eczema (n = 46) [Figure 1]. In our study, majority of the patients (n = 38) developed up to two episodes of eczema per year [Figure 2]. The mean number of episodes per year was 2.66 ± 1.78. The mean score DLQI, in our study, was found to be 9.92 ± 2.42. Majority of the patients (n = 40) had DLQI scores between 6 and 10 [Figure 3]. None of the patients had DLQI of more than 20. The mean HECSI score was found to be 20.38 among males and 16.07 among females, the overall mean HECSI was 19.52. Majority of the patients (n = 33) had HECSI scores between 11 and 20 [Figure 4]. None of the patients had HECSI of more than 50. The mean values for DLQI and HECSI scores among males and females are summarized in [Table 2]. No statistically significant difference was found between males and females in terms of disease duration, number of sick leaves taken, number of annual episodes, DLQI scores, and HECSI score.

| Parameter | Categories | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex distribution | Males | 52 | 80.0 |

| Females | 13 | 20.0 | |

| Age group (years) | <25 | 0 | 0 |

| 25–30 | 10 | 15.4 | |

| 31–35 | 16 | 24.6 | |

| 36–40 | 27 | 41.5 | |

| 41–45 | 9 | 13.8 | |

| 46–50 | 3 | 4.6 | |

| History of atopy | Present | 11 | 16.9 |

| Absent | 54 | 83.1 | |

| Duration of disease (months) | <6 | 22 | 33.8 |

| 7–12 | 22 | 33.8 | |

| 13–18 | 13 | 20.0 | |

| 19–24 | 5 | 7.7 | |

| 25–30 | 2 | 3.1 | |

| 31–36 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Morphological patterns | Hyperkeratotic palmar eczema | 33 | 50.7 |

| Chronic dry fissured eczema | 23 | 35.3 | |

| Nummular eczema | 5 | 7.69 | |

| Mixed pattern | 3 | 4.61 | |

| Vesicular eczema with recurrent eruption | 1 | 1.53 |

| n | Mean | SD | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of disease (months) | ||||

| Male | 52 | 11.35 | 7.63 | 0.342 |

| Female | 13 | 9.15 | 6.45 | |

| Total | 65 | 10.92 | 7.42 | |

| No. of episodes/year | ||||

| Male | 52 | 2.73 | 1.81 | 0.671 |

| Female | 13 | 2.38 | 1.70 | |

| Total | 65 | 2.66 | 1.79 | |

| No. of sick leaves | ||||

| Male | 52 | 1.90 | 1.64 | 0.374 |

| Female | 13 | 1.46 | 1.33 | |

| Total | 65 | 1.82 | 1.59 | |

| DLQI score | ||||

| Male | 52 | 9.86 | 2.232 | 0.710 |

| Female | 13 | 10.15 | 3.184 | |

| Total | 65 | 9.92 | 2.42 | |

| HECSI score | ||||

| Male | 52 | 20.38 | 9.884 | 0.141 |

| Female | 13 | 16.07 | 6.448 | |

| Total | 65 | 19.52 | 9.41 |

DLQI: Dermatology life quality index, HECSI: Hand Eczema severity index, SD: Standard deviation

- Number of sick leaves.

- Number of episodes of eczema per year.

- Dermatology life quality index scores.

- Hand Eczema severity index scores.

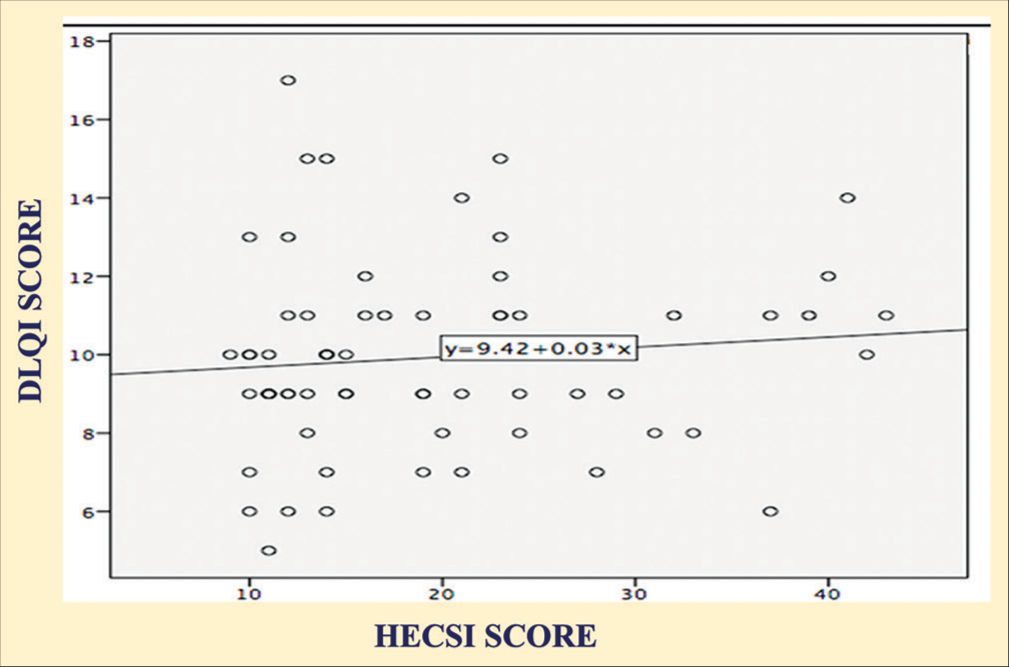

A positive correlation between DLQI score and HECSI score was found in our study, but it was not statistically significant (P = 0.247) [Figure 5]. We also found a significant positive correlation between DLQI score and number of sick leaves (P = 0.005), while correlation between HECSI score and number of sick leaves was not found to be significant (P = 0.060) [Figure 6]. In our study, a positive correlation was found between disease duration and DLQI score (P = 0.011) and HECSI score (P = 0.002) and it was significant [Figure 7]. Furthermore, the correlation was positive and significant between number of episodes of hand eczema per year with DLQI score (P = 0.003) and with HECSI score (P = 0.056) [Figure 8].

- Correlation between dermatology life quality index score and hand eczema severity index score.

- Correlation of number of sick leaves with dermatology life quality index score and hand eczema severity index score.

- Correlation of duration of disease with dermatology life quality index score and hand eczema severity index score.

- Correlation of number of episodes of hand eczema per year with dermatology life quality index score and hand eczema severity index score.

DISCUSSION

Lock making is a complicated process that includes electroplating, spraying, dyeing, cutting, grinding, polishing, packaging, and others. The people engaged in this process are day laborers whose only source of income is lock making. Individuals of various ages, including children and women, make up this group. They are exposed to different kinds of chemicals which may cause, precipitate, or worsen hand eczema. We conducted this study, to assess the impact of hand eczema on the QoL in lock makers.

In our study, we found that a much greater number of males (80%) were affected as compared to females (20%). More number of females were found to be affected in studies on hand eczema from India by Kataria et al.[9] (55% females) and Charan et al.[10] (52.1% females). Studies on occupational hand eczema from the western countries have shown greater involvement of either sex.[3,11] Sex predilection in hand eczema may depend on the type of work and participation of females in the labor workforce.

The most prevalent age group affected in our study was 36–40 years (41.53%) with a mean age of 36.65 years. The involvement of the middle age group is expected due to their participation in the workforce. The previous studies on occupational hand eczema have also indicated the involvement of people in middle age group.[12] The involvement of this age group is troubling as it must put a heavy economic and social burden on workers and society as a whole.

Atopy was present in around 17% of our patients. Contact sensitization and a history of atopic dermatitis have long been recognized as risk factors and are associated with poor prognosis. The severity of hand eczema at the time of presentation is another risk factor, with disseminated hand eczema suggesting a bad prognosis, and early age at onset is also associated with a poor prognosis.[13-15] In addition, recent studies have shown that stress, inactivity, and smoking have a deleterious effect on prognosis.[16,17] The mean duration of disease in our patients was 10.9 months. Hand eczema is a chronic ailment, but is punctuated with phases of clearance. Mälkönen et al. also found that occupational hand eczema was present in the majority of patients for less than a year before presentation.[11] Early presentation indicates a high level of concern for the signs and symptoms in the patients. Most patients (58.5%) had up to two episodes of eczema per year, while 18.5% patients had five or more episodes of exacerbations per year. This figure highlights the chronic and relapsing nature of hand eczema.

The number of sick leaves for hand eczema in lock makers was usually less than two, females took an average of 1.46 leaves, while males took 1.9 leaves on an average. The number of days lost from work is much higher in studies from the west with as much as 76.4 days lost in the last year in a study from Germany.[3] Males and females were likely to have similar days of sickness absenteeism from work in another study.[18] The extreme contrast of sickness absenteeism seen in our study may be due to the fact that lock making is usually a small scale industrial work where workers cannot afford to lose work due to no social security and poor implementation and awareness of labor laws. Females are further vulnerable and this may have resulted in their lower absenteeism from work. For most workers, the days of work were lost due to visit to the hospital for their skin disease.

In our study, the mean DLQI score was 9.92 ± 2.426, signifying moderate to large effect on QOL. Similar DLQI values were obtained by Charan et al.[10] (DLQI score 9.54 ± 5.62), Kataria et al.[9] (DLQI score 8.18 ± 3.4), Yu et al.[19] (DLQI score 8.39), and Agner et al.[20] (median DLQI score 8). The DLQI was slightly lower among males than females in our study. Mollerup et al.,[21] in their study on 306 patients with hand eczema, found that the impact of disease is greater in females and they experience greater impairment in their life quality, though the severity of hand eczema is same. The mean HECSI score in our study was 19.52 ± 9.416. Agner et al.[20] found almost similar mean HECSI value of 17.0. They too found that males had more severe eczema (HECSI score of 20.5) than females (HECSI score of 14.5).

In our study, we found no significant association between hand eczema severity and QOL (P = 0.247). Similar results were obtained by Charan et al.[10] (P = 0.078). We found that patients with less severe hand eczema sometimes had significant negative impact on their QOL. Contrary to our study, significant correlation was found between DLQI score and HECSI score, in the studies done by Kataria et al.[9] (P = 0.001), Agner et al.[20] (P < 0.001) and Yu et al.[19] (P < 0.05).

We found that the duration of disease correlated with DLQI and HECSI score. However, Charan et al.[10] and Yu et al.[19] did not find any correlation between these parameters. Thus, one may conclude that duration of disease does not affect severity of eczema or QOL. In our study, we found that the number of episodes of eczema correlated with DLQI but not with HECSI score. Similar results were obtained by Charan et al.[10] in their study. Thus, QOL is adversely affected with greater number of episodes of eczema experienced by the patient.

In our study, we found, a significant association of number of sick leaves taken with DLQI but not with eczema severity. Similar results were obtained by Agner et al.[20] in their study (P < 0.001). Charan et al.,[10] on the other hand, did not find statistical correlation between days of absenteeism from work with either DLQI or HECSI score. In hand eczema patients, sick leave is determined not by QOL or severity of eczema alone, but also by the type of work, individual variations, economic status of the worker, and the availability of health facilities to them.

Limitations

This was a hospital-based study, so the actual severity of hand eczema and its effect on their QOL cannot be extrapolated to the general population of lock workers. We were not able to determine whether the dermatitis was allergic or irritant as we did not perform patch testing due to financial constraints. Further, the lack of patch tests means the common allergens causing hand eczema in lock workers could not be determined.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that the lock workers with hand eczema had considerable impairment of their QOL. They have loss of workdays which may lead to economic loss to this already poor section of society. There is a need to identify the processes which predispose these workers to hand eczema and provide preventive and remedial options to these workers. An early and prompt intervention is needed to minimize the disability and impairment and to improve their health.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Guidelines for diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hand eczema--short version. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:77-85.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hand eczema and quality of life: A population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:397-403.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cost of illness from occupational hand eczema in Germany. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;69:99-106.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review of cost-of-illness studies in hand eczema. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:67-76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient reported outcomes to support medical product labeling claims: FDA perspective. Value Health. 2007;10(Suppl 2):s125-37.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Translating the science of quality of life into practice: What do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:659-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The hand eczema severity index (HECSI): A scoring system for clinical assessment of hand eczema. A study of inter-and intraobserver reliability. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:302-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A cross sectional study to analyze the clinical subtype, contact sensitization and impact of disease severity on quality of life and cost of illness in patients of hand eczema. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:663-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of hand eczema severity on quality of life. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:102-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long term follow-up study of occupational hand eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:999-1006.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety, depression and impaired health-related quality of life in patients with occupational hand eczema. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;67:184-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hand eczema-prognosis and consequences: A 7-year follow-up study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1428-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fifteen-year follow-up of hand eczema: Predictive factors. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:893-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hand eczema extent and morphology-association and influence on long-term prognosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2147-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Associations between lifestyle factors and hand eczema severity: Are tobacco smoking, obesity and stress significantly linked to eczema severity. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:138-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing prognosis for occupational hand eczema: New trends. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1280-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severe occupational hand eczema, job stress and cumulative sickness absence. Occupational Med. 2014;64:509-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The quality of life and depressive mood among Korean patients with hand eczema. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:430-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hand eczema severity and quality of life: A cross-sectional, multicentre study of hand eczema patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:43-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An analysis of gender differences in patients with hand eczema-everyday exposures, severity and consequences. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:21-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]